“You try not to think about the past and you try not to think about the future…I was not expecting detention to be a part of my journey and it really affected me psychologically for a long time. I lost myself. The way I thought about a civilized community, it changed.”

32-yr-old asylum seeker from Afghanistan. Detained in Greece & Turkey for 11 months.

EUROPE

Across the table from me inside the detention center at the Rome airport, a Palestinian man told me, “Every time I come here, my health gets worse.” He had lived in Italy for over thirty years. It was his seventh time being detained.

Tucked away in the mountains of northern Greece, a guy from Pakistan looked at me and said, “I don’t know why I have been in here so long.” His fingers were clenching the high metal fence that confined him in what can only be described as an open-air prison camp.

With his asylum claim rejected yet again, a man from the Democratic Republic of the Congo shared a thought about the six months he spent in two detention centers in Belgium. “Detention here was psychological torture,” he said. “Now, I don’t go outside much.”

On a rooftop in Malta, I stood with a man from Sierra Leone. A group of pigeons swooped overhead. He looked at the birds, closed his eyes and then he smiled. I could only imagine where his thoughts took him at that moment. “I felt like I would never get out of detention,” he had said to me earlier that day. He had spent almost two years in detention.

And, in the Netherlands, a man from Myanmar (Burma) watched two of his children play together. From the outside, this apartment-like complex where he and other families seeking asylum had been placed didn’t look like a detention center. However, with all the rules, restrictions, monitoring and control imposed upon them, it was just another form of detention dressed up as being more humane. “I feel like it’s a prison,” he said. “Mentally you become sick day by day.”

In the European Union and the broader (46-member) Council of Europe there are numerous regulations, directives, treaties and laws that regulate member-states responsibilities toward migrants, refugees and asylum seekers, including with respect to the use of detention. While member states are bound to these policies, their implementation (or lack of implementation) can vary widely from country to country.

Detention center. Removal center. Transit zone. Reception center. Closed center. Open center. Pre-Removal center. Police station. Border station. Prison. Hot spot. Tent village. Asylum seeker center. Family location. Across Europe, the use of immigration detention—in its various guises—has intensified and expanded since the 2015 migrant crisis. It has also grown in neighboring regions, often backed by European funding—and pressure—including in countries like Libya and Turkey, with the intention of preventing migrants and refugees from reaching Europe’s borders.

The idea for the project Seven Doors began in Europe. The people I met were not fleeing from somewhere. Many had been settled in Europe for years, if not decades, often deprived of a nationality and stateless, hence lacking documentation and legal status. For them, life had become a traumatic cycle of detention and the fear of detention. Their stories were unlike any I had heard before.

At the same time large numbers of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers from the Middle East and Africa were desperately turning to Europe for safety and a better life. Would these European nations expand their deliberate use of immigration detention to inflict yet another traumatic experience into their journey? The answer is: Yes. And now, years later, it continues to be, Yes. Those turning to Europe for protection have higher expectations. Additionally, the compassionate and dedicated individuals in this chapter who work to extend empathy and human dignity to people caught in systems designed to do everything to strip that humanity away, have higher expectations as well.

Several things have become clear throughout the years of working on this project: When the use of immigration detention is prescribed and entrenched into policy, states push the boundaries of its use as far as they can; more times than not, states will use detention to harm people. When it comes to detention, Europe, despite its promise of a better, more just union and open boarders, turns out to be little different from other places.

Amygdaleza Pre-removal Detention Center is located in Athens, Greece. Built in 2012, the detention camp is notorious for substandard conditions, abuse and the detention of children. It can detain up to 1,000 immigrants per day.

“The first time to get to Europe, we had an unsuccessful journey. I was caught by the Turkish police. They kept me in detention for six months in Turkey.

“I was deported back to Afghanistan. After some time I decided to come back. I decided to take the risk. I couldn’t stay in Afghanistan. Greece was not my final destination, but I had no choice. It was stay here or return home. I was in a detention center for almost three months in the north of Greece, then I was transferred to another detention camp where I stayed for almost two months. There, it was very difficult.

“The most tiring thing is that every day you sleep in your bed, wake up, eat your food, and you have to go back to sleep in the same place and there was no space to do anything else. No sense of how long you would be there.

“Our faces were tiring to each other. It was not nice to see each other’s faces because for sixty days when you sleep and wake up, all you do is see the same tired person in front of you. For the first week it was ok, but after that, it was very heavy.”

“I was a very social person before all of this. Now, I feel like I should stay away from people. I’ve isolated myself. I do not interact with people. I think this is the gift I got from that detention center.”

32-yr-old asylum seeker from Afghanistan. Detained in Greece & Turkey for 11 months.

Originally from Sierra Leone, this man spent years traveling through Africa to get to Europe. His boat was intercepted in Malta where he spent almost two years in detention.

“Having citizenship was the best thing I was thinking of when I was in detention and in fact, when I arrived in Malta, I was thinking that, This is the place where I will be given a document. That, He is from here. We want him here to be his home.

“But when I received the first reject and you are in detention, it means there is no home for you again and it is devastating. I felt like I would never get out of detention. After one year two months that I spent in detention, at the time I was let out, like they said, Freedom. But it is still not freedom, cause you cannot move from here to anywhere. You are still on the island. It’s like you are still in prison.

“I feel like I’m not living the same way as other people are. Cause I see people moving, going up and coming. People traveling. I see the planes flying everyday. In the sea, I see this ship traveling the sea. People going from country to country, which I never have the access to do. So for me, it’s like my whole life, it’s been, it’s been stopped.”

Asylum seeker from Sierra Leone. Detained several times for almost 2 years

Born in Myanmar (Burma) and from the Rohingya ethnic community, this man fled to Bangladesh, then he was smuggled into Holland. After his request for asylum was rejected for the second time, he was immediately put into immigration detention. The detention was incredibly traumatic and contributed to on-going medical and mental health issues. For a period of time he lived temporarily in an old jail in Amsterdam that had been turned into a short-term housing facility for aliens, asylum seekers and the homeless.

“All of the things that have happened to me, I can’t do anything about. I’ve been powerless. You hear how living in Europe is living in the best part of the world. But now I am here, and I have nothing.

“What do I have to say about my feelings? I can’t say anything. I have nothing. I have to take a pill to fall asleep at night. I have high blood pressure. What is there left to say about my feelings? We are all the same. We have blood running through our veins. But the difference is I don’t have a simple card called an Identity Document. If I go outside and the police want to talk with me and ask me for my ID, I don’t have anything and they will put me in detention. If they talk with you, you can have a chat and then continue. I can’t go outside without fears of being detained and put in detention.

"I feel like I am ball where I am going from one place to another, from another to another. I have absolutely no control over my own life. The asylum procedure has been just a big game. People were not recognizing and talking about my actual problem."

27-yr-old asylum seeker from Myanmar

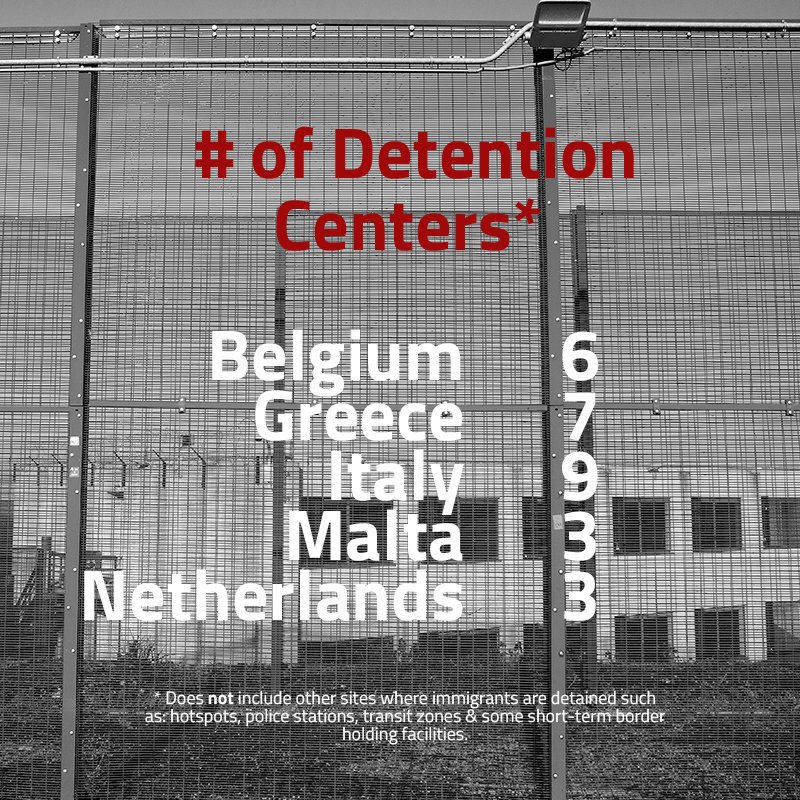

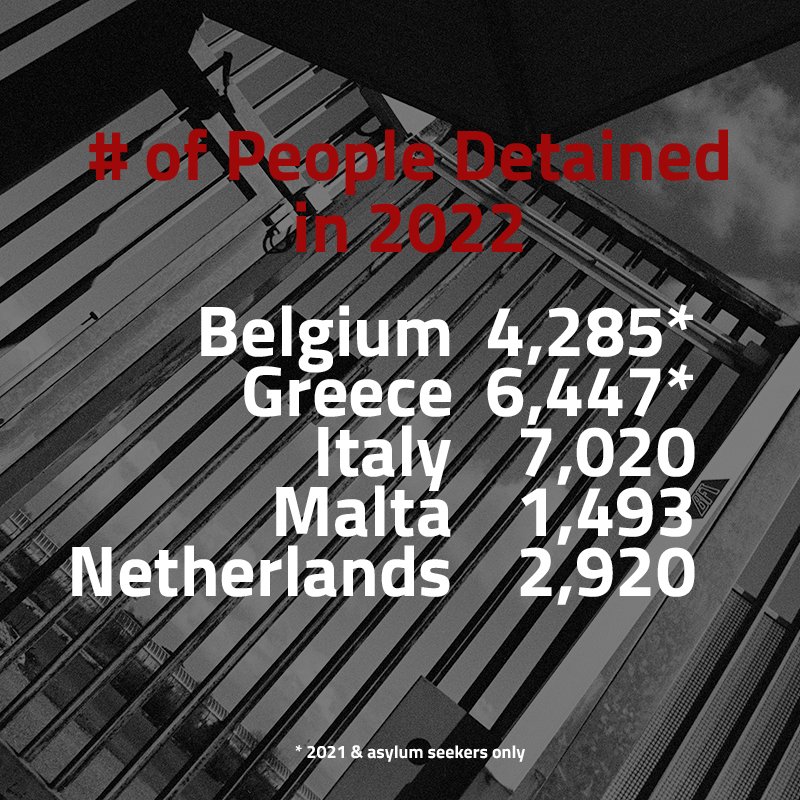

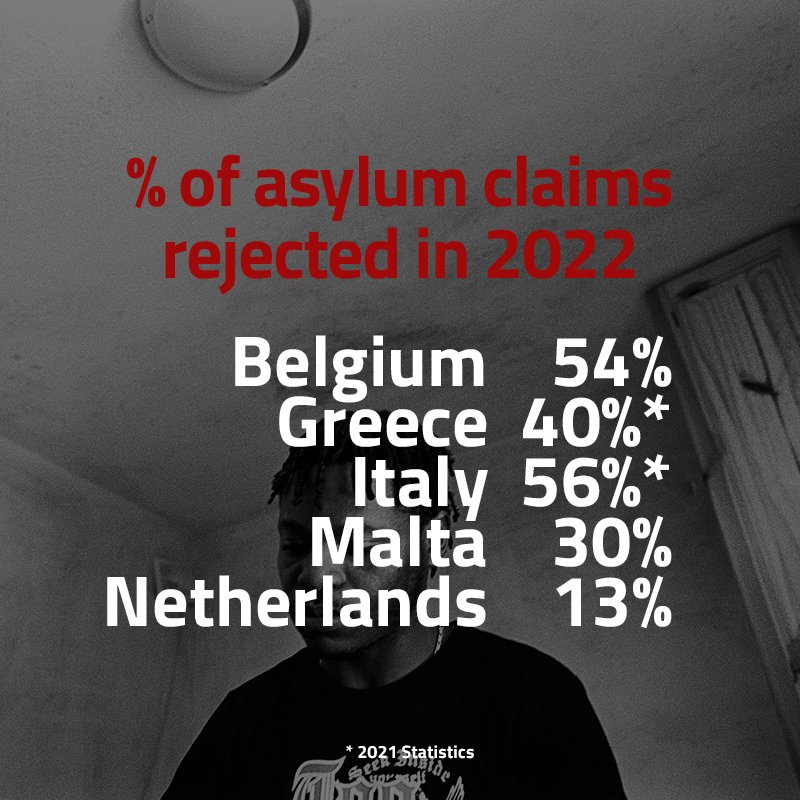

THE NUMBERS

Source: As highlighted by the Global Detention Project in its 2020 Annual Report, the European Union statistical office, Eurostat, collects extensive data related to immigration enforcement in the EU. However, it does NOT collect data on immigration detention. With insufficient statistical reporting and a lack of transparency from governments, one should ask: How many thousands are not represented in these numbers?

All the statistics above were sourced from AIDA/ECRE, PICUM, CILD & Global Detention Project, as well as correspondence with several local organizations in each of the countries listed above.

The Paranesti Pre-removal Detention Center was built in 2012. It is located inside an old military base in the small and remote mountain village of Paranesti in the Drama region in north-east Greece. It detains up to three hundred men per day.

“I’ve been in here for three months. They said they could keep me in here for 18 months! One month ago, they said they would call about my appeal but that never happened. Now winter is coming and we need warmer clothes for it. No one wants to leave their family but we had to. We left everything behind for our families.“

28-year-old asylum seeker from Pakistan. Detained for 3 months

“I’m married to a Greek woman. I’ve tried so many times to apply for asylum but they continue to reject me. I don’t know why, and I don’t know why I am in here? But, I’ll wait in here and I’ll try again.”

33-yr-old asylum seeker from India. Detained 3 month and 10 days

“I arrived in Greece in 2018. That’s four years ago! My asylum application has already been rejected two times. I’ve been detained in several police stations, each time around five days. I was detained in another camp for over one month. Now I’m here. I’ve been here for two months. It’s just too much stress. I still don’t know why I’m here and I don’t know how long they will keep me here. I’m just waiting.”

33-yr-old asylum seeker from Democratic Republic of the Congo. Detained for almost 7 months

“One of the most central things I deal with is the trauma detention has on the people I support. I have seen firsthand how it causes stress, insecurity, despair, feelings of helplessness and feelings of depression. The impact of detention or the fear of detention, the mental health impact is huge.

“I have seen from people who have been detained and released how haunted they are or how afraid they are by the idea of maybe being detained again in the future which can be deeply traumatizing and stressful. That sense of not being free, of being detained again, it manifests in various ways.

“Unfortunately, it has a paralyzing affect. Many times, people who are afraid of being detained have lost or do not have access to legal documents. So on top of the fear of losing their freedom, their social support system almost always collapses. It’s a dynamic combo and exacerbates their situation even more and it really complicates the mental torment that people who are in fear of being detained are experiencing.

“People have been through a huge trauma and difficulties in their home countries, but they are very resilient because of that. The fact that people are again traumatized by the fear of detention or actual detention when they reach Greece can be debilitating.

“We have seen some people who have never had severe mental health problems actually develop mental health issues or disorders while in detention or while they are in this limbo of being afraid of being detained.

“Often times, when the case is in a legal dead end or if there are other things we can’t do, I am probably the only person that they can grab on to for some kind of hope. It’s something that always makes me want to be as ‘human as possible’ because often times you see they have no one or almost no one.

“It can be really powerful and at the same time a huge responsibility to be in the shoes of that person who needs to guide them or help them or support them or even just be there for them, listening to what they have to say, expressing themselves, hearing their story, trying to empathize with them.”

“I think my role in some cases is really central. In a way you become so focused and invested on trying to help in any possibly way, it does take a toll. “

Panos, Psychologist, HumanRights360

127Bis Detention Center located adjacent to the airport in Brussels, Belgium.

“I left DRC because I worked for a human rights organization. At home, I was detained three times. The first time was for three months. I was tortured. I was detained three weeks the second time and again for four months.

“When I arrived here in Belgium, I immediately knew I could ask for asylum, so I did. And then they immediately put me in detention. I never ever thought I would be put in a prison. It’s a prison. It’s not a detention center. I was in Caricole for two weeks and then in 127Bis for almost five months.

“I had no idea how long I would be in detention. The reason why I got out after 5 months was because a judge annulled the negative decision. The judge said there was no reason for me to be incarcerated, that I should be free to work on my asylum claim out of detention. I asked myself, Why was I detained? I lost time! It wasn’t right. It’s not normal. There are people I know who have been detained for nine months or even a year. There’s no answer!

“In Congo, I thought about two guys who were in my cell. At night they were there. In the morning, they were gone and you never heard from them again. I can expect this in Congo. Detention in Congo was physical torture.”

“But what happens in Belgium, I did not expect. Detention here was psychological torture. To be treated like a criminal here in Europe…I didn’t expect it at all.”

42-yr-old asylum seeker from Democratic Republic of the Congo. Detained nearly 6 months

“I saw the life for me in Europe, and I saw I would be safe and have a life. I came to Belgium and was detained for nothing.

“I looked out and there were two police cars. I go with them and they say, Sign here! I signed because I hadn’t done anything wrong or had not caused any problems. I didn’t have any problems in Belgium. I would work and go home. Work and go home. After 1-2 hours in the car, I didn’t understand where the police were taking me. Then we got to the detention center.

“They tried to deport me to Greece. They took me in a car with my hands cuffed and they took me to the airport. Six policemen took me to the flight. The captain came and talked to me, and I said, The police want to send me to Greece and I have no control and I can’t go! If I go, I will kill myself! The captain told me to relax and then he went to the police and told them he wouldn’t take me. Then they took me back to the detention center.

“I was in detention for months. The months felt like years. Every month, felt like one year. After that time I was so tired. I stopped eating and drinking.”

“Back at home, there were bombings and fire and killings all the time. If someone gets in trouble, even there in that place, there is a judge and they can make a decision about you. And you know what will happen. Even in that place there is a system. You understand what happens. Here, the months in detention you don’t know. You don’t have a decision. You don’t have anything. The people just play football with your life.”

37-yr-old asylum seeker from Palestine. Detained for 7 months

Ruben and a colleague make the walk out to the Caricole Detention Center near the airport in Brussels, Belgium. Next to Caricole is Belgium’s largest immigration detention center, named 127Bis. In 2022, the two detention centers detained more than 2,500 people.

“There are a huge amount of emotions that go through me. I do the walk every week. I go from Brussels on a train, then to a small village center, and then into those fields and all that’s left are these concrete walls and chain link fences. I feel like I’m physically detaching myself from civilization in almost a literal sense.

“As soon as I press the doorbell at the front gate, I know from now on, it’s no longer in my head or it’s no longer my thoughts. Before, I have that calm. But as soon as I press that button, you have to expect the unexpected. You have to turn on all your senses and really pay as much attention as you can to everything, because it is all about these very small details in what people share with me.”

“I feel like I bring some humanity to the centers. I feel that’s the primary reason for me to be there. It’s the difference between not seeing them as part of a ‘file’ or as part of a ‘case’ like anyone from the government sees them. I try to challenge some of the cruelty inside that system in giving them back a name, giving them back a full story, rather than seeing them as people who don’t have documents. That gets connected to all these kinds of prejudices. What we do is come and listen without the prejudices.

“Sometimes I wish like I could just scream out all the injustices. But you are also realizing that maybe it wouldn’t make a difference. Maybe once I start screaming out these stories, the world will just not listen or care. I think that is a very different realization. You can’t add more stories and expect a moral outrage about these things. The system will just continue because it is just so ingrained.

“And that makes it difficult to realize that I’m not doing this to necessarily be the one that changes everything. I’m doing this because I feel it’s necessary that there is someone doing it, and I want to be that person.

“I find this an evil system but I don’t find Belgium an evil country. So, I wonder at what stage do you develop a system that becomes evil? What is the motivation behind upholding that system? What goal does it serve? Nobody knows about this and nobody seems to care.”

Ruben, Accredited Visitor

Top: (L) Schiphol Detention Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. (R) Centro di Permanenza per il Rimpatrio (CPR) in Rome, Italy. Middle: (L) Petrou Raili Family Pre-Removal Center, Tavros, Athens, Greece. (R) Center for Illegals, Bruges, Belgium. Bottom: Amygdaleza Pre-Removal Center, Athens, Greece. (R) Xanthi Pre-Removal Center, Xanthi, Greece.

"I have not seen the sun for a month. They sent me back here again. I did eight months in the center. Then they let me out and I went to sleep under bridges. Then I went to the hospital because I got sick. When I was released from the hospital, they took me again and put me in detention."

“I used to live with an Italian woman. We were together for almost 15 years. Then she left me. How can I blame her? I was always here. They kept bringing me here. How could I give her enough to live? How do you think I’m feeling now? I always feel sick. Every time I come here, my health gets worse."

52-yr-old Palestinian man. Detained 7 times in Italy

This 46-year-old man was born in Uzbekistan and for a number of reasons, became stateless after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Since the mid-1990s he tried to secure citizenship but faced hurdles in doing so. He has lived in Holland for over 13 years and has been in detention multiple times. For years he lived on the streets, which resulted in going in and out of detention. He was detained for three months after he was asked to show his ID by two police officers while he was walking his dog. When I met him, he hardly left the apartment.

"In total I've probably spent about three and a half years of my life in detention. I got two weeks punishment for stealing trousers, but for being undocumented, for not having a passport, for being 'undesirable', I've been punished for years.

“I can't trust people anymore. It doesn't matter who you are. Detention changed me. My wife calls me an oyster. You're always shut, she says. I used to be cheerful, but I'm grouchy these days. I can see it myself. I don't just feel stateless, sometimes I simply don't know who I am anymore."

46-yr-old asylum seeker from Uzbekistan. Detained three and a half years.

Rotterdam Detention Center

“I just want to be there and that’s it. I just want to be there, that day, so they know there are people who think of them.

“The people in detention, they appeal for your feelings. But we can’t help them. And that costs a lot to us. We say, We can’t do anything about your situation, but we can be here now and talk with you at this moment. I’ve come just for you this hour. I’m a listening ear.

“I think people outside don’t understand at all. It’s a great problem. People don’t want to see it to protect themselves. Sometimes you become depressed because of the system in which we live. We don’t want to accept it, so we try to give something back to the people who need it.

“Some time ago something happened that shocked me very much. I went to visit a man. I’ve visited him many times, and this time I had to wait and wait to visit him. I asked, Why doesn’t he come out? Why don’t you bring him down? And they said, He’s not in the building anymore. And I asked, Where is he now? And they always say, We are not allowed to say.

“I said, I want to know because I come and visit him many times. Where is he now? And then they used a word, We put him on transport. And that’s exactly the word they used in the Second World War to take the Jews to the concentration camps. We put him on transport. So they used the same words for a detainee. I became angry and I said, I never want to hear that word again! It shocked me.”

“Its overwhelming all the bad things. Sometimes it is too much, but sometimes there is this little light and you think, How is it possible in all of this? It’s important to notice this and that gives a little hope. Those small things. You have to try to notice those good moments. We have to celebrate those good moments, for you and especially for the person you are visiting.”

“Before the first time I went to visit someone in detention, I asked the pastor, What do I do? What do I have to say? And he said, Just be there. Don’t ask anything.”

“So I went, and on that first visit I met a big man from Cameroon. I said, I’m here. And we sat and we didn’t say anything to each other. To me, it seemed like ages, but it was maybe three, four, five minutes. And all of a sudden two big tears came to him and down his face. And then I said, It’s difficult, isn’t it? And he started talking. The silence was…I can’t describe. It was just being there. Just being there. And I visited him for half a year.”

Visitation group, Asylumseekers Rotterdam

“When I arrived in Holland, I was in a place for a week or so, then I went to an asylum camp for three months. And then I went to another camp. There, immigration said I had to go back to Lebanon. They said I didn’t have the right to stay here. I said, I cannot go back!

“The police came to the camp and arrested me and took me to a detention center. I was in the detention center for three months. After three months, they let me go.

“Some time after I was released, I met a woman and I got married and had a son. My wife told me to try to go through the immigration process again. I went to immigration and told them I have a son here and I cannot leave and that I want to file asylum again. I waited two years to get an answer. When I went back to immigration for another appointment, after five minutes of talking, they brought out the police and sent me off to detention again. I said, You know I have a son. Why are you doing this? If I have to leave this country, I will lose my son. I was in detention for another nine months.

“My lawyer talked to immigration and they let me see him once in the nine months. Seeing him gave me hope, but I lost custody of him when I was in detention.

“The first time in detention was really difficult because I had never been arrested before. The second time, I was like, I can do two or three months. I can deal with that but then it was six months and it was really hard mentally.

“When immigration comes and has these talks with you, they say you have to go back to your home country. You say, No, no, no.

“Then they start to put more and more pressure on you each month. If you want to go back to your home country, we will release you. It becomes difficult.

“You start to feel more. You start to think a lot. What should I do? Should I say yes or no to that? But I would always tell myself, No. You can’t go back! And they would say, Ok, we’re going to detain you longer.

“I never got to the point where I would give up. Five months. Six months. Nine months. I would go through it.”

53-yr-old Palestinian asylum seeker from Lebanon. Detained one year.

The organization, Meldpunt Vreemdelingendetentie from Stichting LOS, operates an ‘Immigration Detention Hotline’. They answer calls and assist immigrants detained in the Netherlands.

“Our purpose is to improve the detention conditions. We would like to see all of immigration detention disappear but unfortunately, there’s no prospect of that and it’s not very imaginable in this political climate to think this will happen any time soon. As long as detention exists, we want to improve the conditions, to try to make it as humane as possible.

“The primary goal of our hotline is when people call, we are there to assist them. We want to hear from them about the conditions, about what is really happening, so we can learn from them and try to improve it. We listen to their stories so we can analyze what kind of signals we get from them and we bring that to politicians or the media so people outside are aware and so they can change the policies.

“It’s really a closed setting and nobody knows what’s happening inside, so because of that, we want to hear their stories. It’s important for us to show our solidarity and let them know there is somebody monitoring things, watching with them and going with them on their journey.

“When we think of migration and also immigration detention, there is a political discourse which is very big, which is the asylum discourse and we talk a lot about refugees and asylum seekers. But there are people in detention who call our hotline who have been here in this country for a long time. Some up to 40 years. They are not on a journey to somewhere. They are already here and they have been here and already have lives here. They will say to you, I am not an alien! How can I be an alien if I have been here this long?

“The days go up and down. In general, this kind of work is frustrating because you want to do a lot but in reality you make just baby steps or even steps backwards. Maybe I want to improve the detention conditions but the political climate today is to maybe make it worse.”

“Some of the stories, they touch you of course because you bond with the people who call you and of course I am also human. For me it’s always important to search for where I can still find some hope because without hope, I think you can’t do the work. You have to hope for it to improve or hope so you can at least monitor and try to make it not get worse.”

Revijara, Immigration Detention Hotline, Meldpunt Vreemdelingendetentie from Stichting LOS

This 32-year old man is originally from Somalia. He arrived in Holland in 2009. He was arrested for not having documentation and then spent over one year in detention. After arriving in Holland, his claim for asylum was been rejected twice. Somalia denied his claim to Somali nationality. Stateless and unable to acquire asylum status in Holland, he found himself trapped in Holland with nowhere to go and no way to regularize his status. Dutch authorities tried to deport him to Kenya in 2012 but could not because he was not a Kenyan national. He lived on the streets of Amsterdam for several years. A tree stands outside an abandoned parking garage outside of Amsterdam. For months over one hundred stateless refugees and asylum seekers squatted in the garage. Many did not leave for fear of being arrested and placed in detention.

Ahmed stands at the gate to the ‘family location’ centre or gezinsopvanglocatie where he and his family have lived for more than three years. Unlike ‘asylum seeker centers’ in the Netherlands, family location centers are meant for refugees whose asylum applications have been denied and who have exhausted all legal remedies.

“I came from a place where we had no freedom. Everything in our life was controlled by others. Here, I came for freedom, but we are controlled and controlled again. I’m a human being and I’m living in this country, in Holland. I’m not in Burma or Bangladesh. I’m in Holland. But, I can’t move forward and I can’t move backwards. Life is like totally stopped.

“People think, You are living for free. You have a house. You don’t have to work. You’re getting everything for free. But they don’t know the truth of how we are suffering in this situation. We are living everyday with so many rules.

“People say, This is an ‘open camp’ because you can go outside and come back. But it’s not. We have to inform every day. We have to tell them when we go and we have to come back again the same day. We can’t stay overnight outside of this place.

“Everyday at 9:00am, the people here have to line up in front of the office to just report and get stamped. We report daily. Here I am. Here is my card. I am here. I am not going anywhere. I’m here in this refugee camp. I’m still here. I’m still alive. When I line up, I feel like it’s a prison. Mentally you become sick day by day.

“Every week we take one day and as a family we go out for 4-5 hours. Then we have to return. And we think, Let’s go home! And for a moment you think, Home Sweet Home. But then reality hits. This is not home. This is their home. They are allowing me to live here but with so many rules. People go home to their house to relax and take a rest. We come back and we feel more depressed and more stressed.”

“When I see people outside, they are moving freely. They are happy with their life. I want to be the same as that. I want to feel that happiness. They have no worries. They have no stress. They don’t have that depression like me. This is the reality.”

“I have been here for seven years. I want a drivers license. I want a bank account. I want to have a job. I want to go home after a hard day of work and see my kids and they are happy to see me, their father who has worked the whole day and comes back home. You have your kids hug you and you can buy things for them. That’s what I want. At least let me be human here.”

Ahmed, Asylum seeker from Myanmar/Burma