“When I arrived at Campsfield, there was a fence, a very big fence. I was so afraid. When I looked inside, I was more afraid. Then when someone told me this is where you are returned to your home country, when I heard this, everything in my mind closed. I was hopeless.”

50-yr-old asylum seeker (undisclosed country). Detained for 9 months.

United Kingdom

“If I lie in bed and think about myself, Why?…Why is this happening? It is not my fault. If it was my fault, I would agree. But I just comply with every step they ask me to do. Sometimes I cry at night if I’m alone. Three and a half years is too much.”

We met in a park. It was March 2017. Originally from Guinea in West Africa, he had left home as a consequence of traumatic events many in the UK could not imagine nor would ever experience. He had a reason for leaving home, and he had a reason for believing the UK was the place where he could seek safety and start a new life. “I heard the UK has the best democracy in the world,” he said. Yet, after arriving, he was confronted with a reality that would push him to the closest he had ever been to a breaking point.

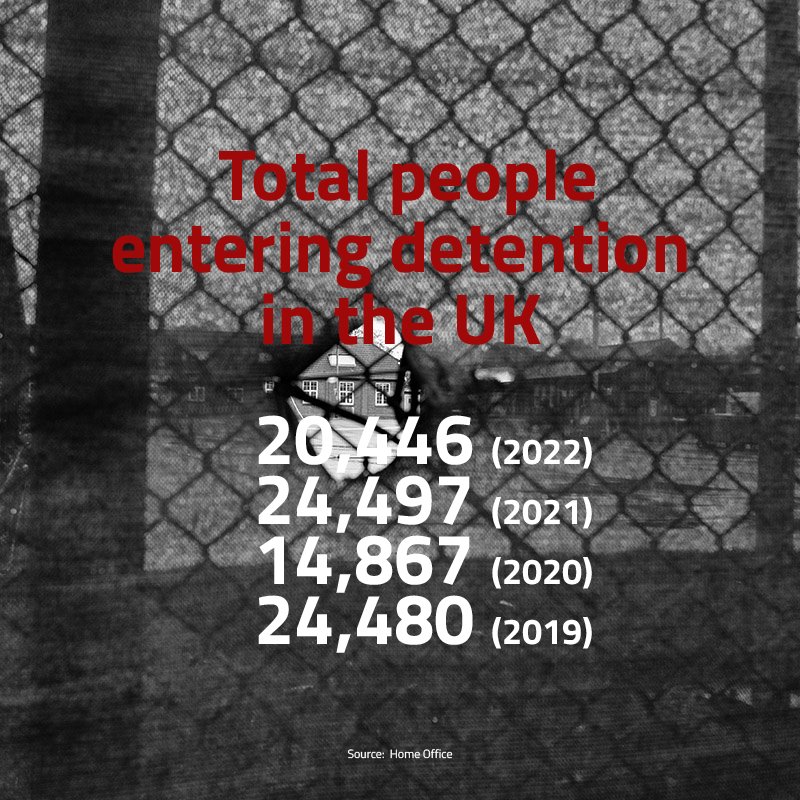

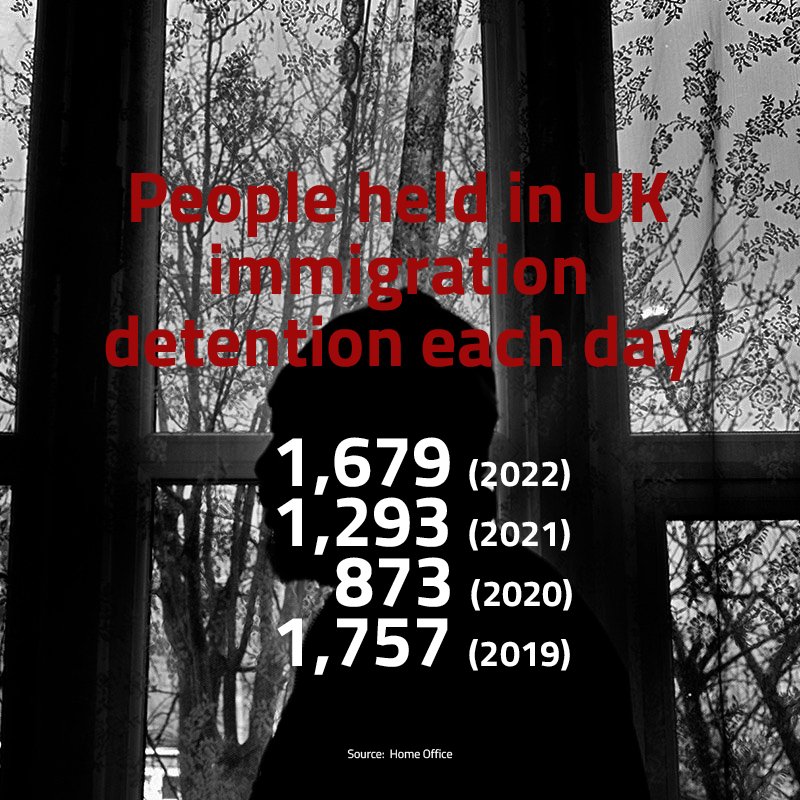

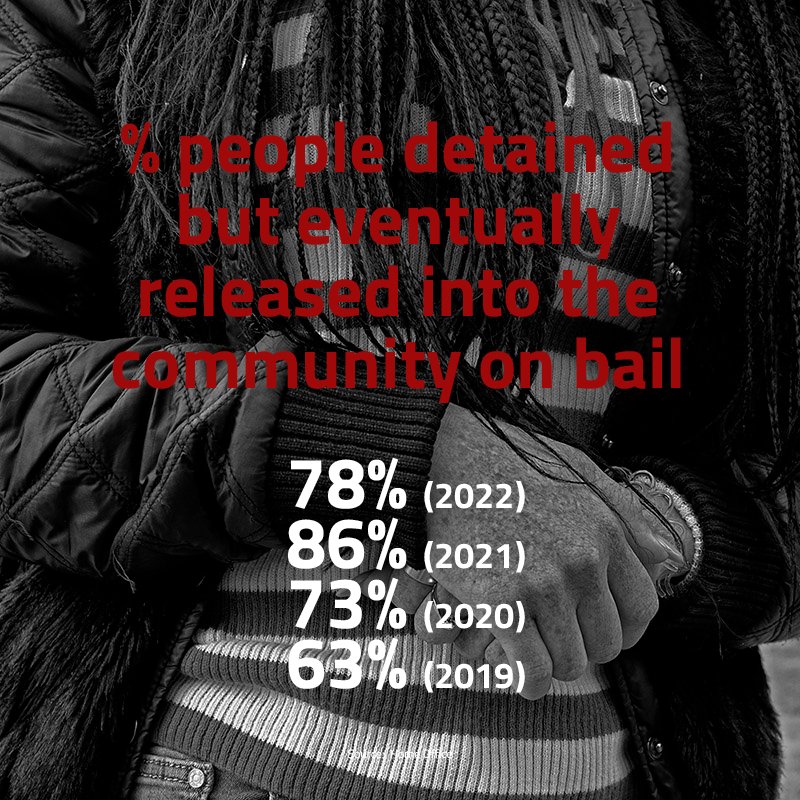

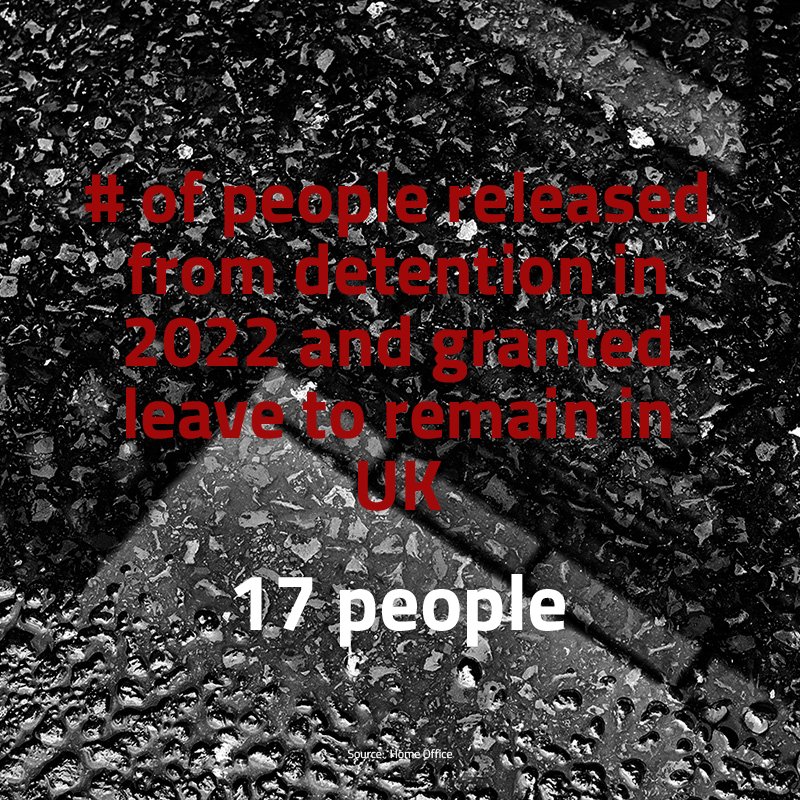

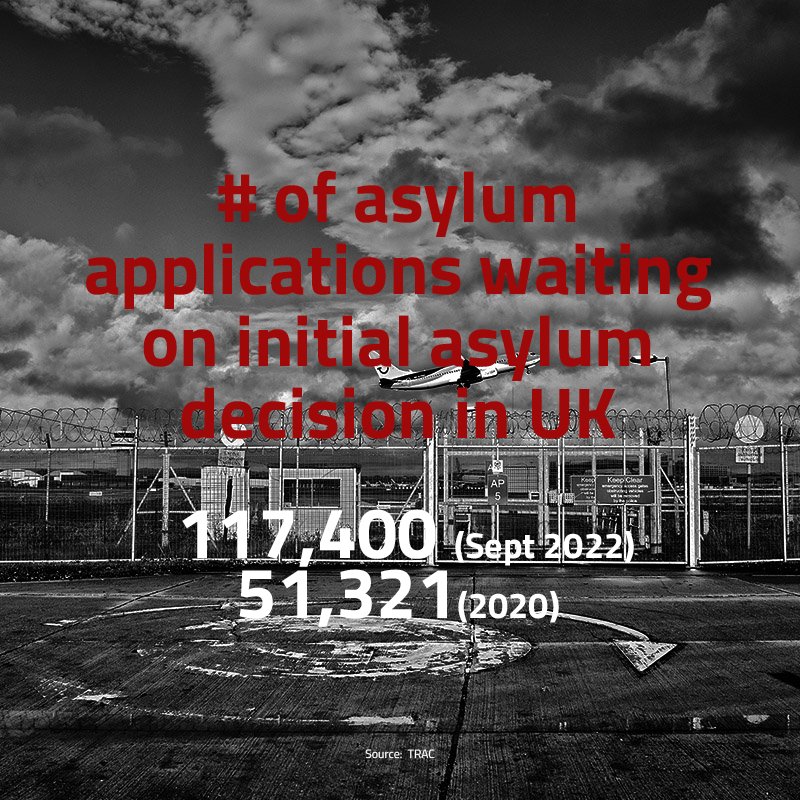

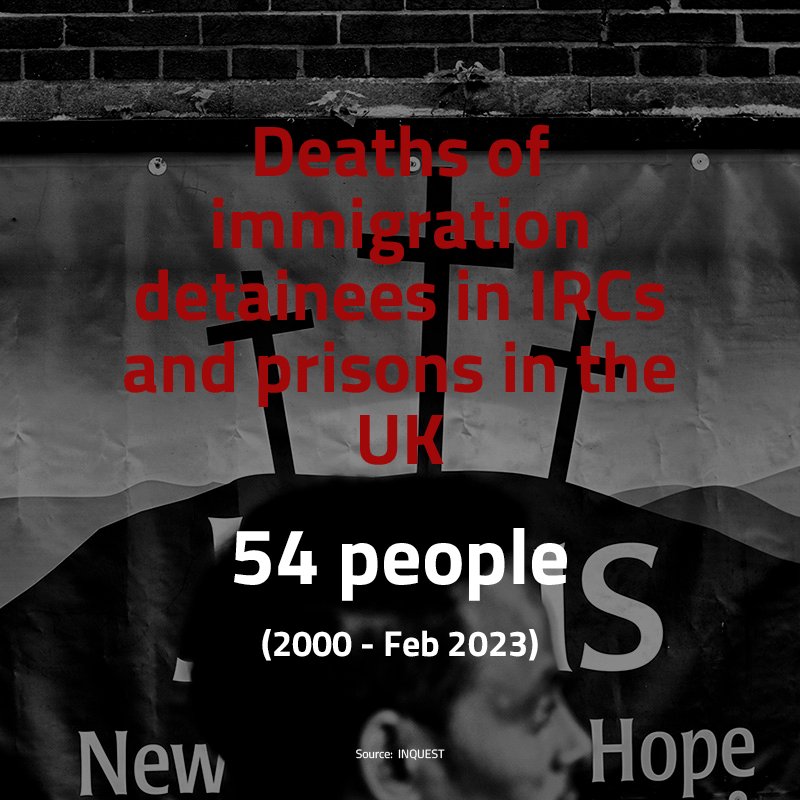

The UK opened its first immigration detention center in 1970 and rapidly expanded its system in the 1990s and 2000s. For years, detention was used to hold people before quickly deporting them. Now, many claim detention has turned into a routine practice of punishing asylum seekers for prolonged periods of time. The UK is the only country in Europe to detain people indefinitely, and its detention estate is one of the largest in Europe. Currently, the UK detains over 1,600 immigrants per day in seven Immigration Removal Centres (IRC), three Short Term Holding Facilities (STHF) and several prisons. A new detention center for women opened in November 2021. Old army barracks and hundreds of hotels house and hold asylum seekers and the Home Office announced the proposed reopening of two additional facilities. In 2022, over 20,000 people were detained in the UK and 78% were eventually released back into the community, leaving one to ask the same question I heard from many men and women in the UK over the past five years, Why?

For this one man from Guinea, detention was like a jungle, “…easy to get yourself into, but nearly impossible to find your way out of.” He had seen people try to commit suicide. Witnessed others struggle with serious mental health challenges as a result of detention. Watched men descend into unimaginable depths of desperation. “Detention is a mental torture,” he repeated several times.

The lasting impact of detention was present with nearly every person I spoke with. I met and sat with people in parks, in cafes, in libraries, in train stations, in the lobby of a hotel and in a parked car. “My life is pending on fear,” one man said to me. Another man was so afraid the only photograph he was comfortable with was of his shadow cast on the side of a building. All of these people had been released from detention, yet I could feel the presence and the fear of the Home Office hovering around, influencing their emotional and mental health and controlling most of the decisions and actions in their lives.

The work for this chapter spans nearly 5 years and was created over multiple trips to the UK. Before the pandemic lockdown, more immigrants were being detained than ever before. COVID resulted in a significant reduction in the use of Britain’s detention estate and of people being detained. After pandemic restrictions were lifted, the UK actually expanded its system, and it didn’t take long for the number of people being detained to reach pre-pandemic levels.

At the time of meeting the man from Guinea, I was just starting the Seven Doors project and I did not have a title for the project. As we talked he described the anguish he continued to live with because of detention as well as his determination to keep moving forward in life. He was incredibly inspiring and his story echoed the experiences of so many others. Still, he made it very clear, the traumatizing experience of detention cannot be confined to the walls of the detention center. It stays and lives with people long after and it filters into families and entire communities.

“When they put me in detention,” he said, “I remember walking through only one door at the detention center. I was in detention for three and a half years. When they let me out, I remember they walked me through SEVEN different DOORS, from my cell to the last door where they said, You are free. But how could I be free? I’m still not free.”

“Those seven doors said, You will not forget this. You will always feel like you are in detention.”

Over one hundred people wait in line to report to Home Office at Becket House reporting center in Southwark in central London in late 2019. Many asylum seekers and people released from detention in the UK are required to regularly report in person to the Home Office at one of thirteen immigration reporting centers.

“When I go to report, I put two pairs of jeans, two T-shirts and my jacket in my bag. Every time. You never know. I go and I say, I’m going to report this day. Be aware of what is happening. It is a mental torture.”

“They control you. Some people have to report once in a week. Still like me, every Friday, when I go, I start and I go in fear that I will not come back. This was my mentality. Because when you go you never know. It is still detention. It is the same as detention. It’s just like a formality. Every week you go in and sign. And there is a long cue.

“Everybody is standing in fear. Sometimes when you go and sign, you come out and you can breathe a little, but still, next week, you have to do it again.”

50-yr-old man from Guinea. Detained for three and a half years

Lunar House reporting center in Croydon, London.

THE NUMBERS

A man fled his home country in West Africa for the UK over fifteen years ago. His home country will not recognize him as a citizen. As a result, he is stateless. Three of his attempts for asylum in the UK were rejected. Home Office tried to deport him three times but the receiving countries would not accept him. He spent over two years in immigration detention. He lived homeless in a forest for six months. Some concerned people provided him with a small apartment. Unfortunately, the stress became too much. While reporting to Home Office he became violent and was detained again. A light hangs in his apartment as volunteers clear out the few personal belongings left behind. In total, he spent 2 years in immigration detention.

“The Home Office first tried to deport me to Mauritania. They put me on a plane with two immigration officials and the Mauritanian authorities said I’m not a Mauritanian national and they could not allow me to stay in the country. They sent me back to the UK. I spent six months in detention.

“Months later, they tried to send me to the Ivory Coast. They put me on a plane again, and I was returned to the UK again. I spent another six months in detention. The third time, I was deported and the authorities said they could not take me back. I was sent back to the UK and spent another six months in detention.

“For someone who has citizenship, at least they can go around and they can start their life again. But me, no country wants to take me back. I have lived here long but I wasn’t expecting to spend two years in detention, like a criminal where everyone is looking at you like you’ve done something severe but you’ve done nothing at all.”

“I feel empty from everything I’ve lost. I’m a broken man and I struggle to survive. Things went so badly. For six months, I lived in the forest, then for six months some people rented a small apartment for me. It’s all a temporary existence.”

“Ten years I’m in the UK. I’ve done everything I can do. I’m not a criminal. I don’t fight with anyone. I do voluntary work and help people. I do this to try and show the Home Office who I am. But, they still don’t believe. They control me. They don’t want to give me peace.

“When Home Office tells me to come in and report, in ten years, I have never missed one day. I go there every single time, sign in and come back again. Two months ago, they said for me to come with my wife and baby, but then they wouldn’t let them come in with me. We didn’t know what would happen. It was terrible.”

“I was in a place for months and you don’t do anything. You don’t speak to people. You just get quiet. Sometimes now, I have the problem when I feel like I just don’t want to talk with anyone. Even now, I feel like I am in detention. The only difference is I’m on the outside. I can see people. Those months in detention, you close in on yourself. “

34-yr-old man from West Africa. Detained for 3 months

The Heathrow Immigration Removal Centre located adjacent to Heathrow Airport in London is Europe’s largest immigration detention center. It consists of two detention centers: Harmondsworth and Colnbrook,

“You feel like you are fighting something but you cannot fight something that is impossible to beat. You cannot fight the Home Office because there are no rules.

“Your life pends on fear. My life is pending on fear. You feel the fear all the time. There are days when I have been terrified to go to report. They can put me back in detention any time. This is a first world country, but when you go into a detention center, you are not in the UK. You are not in a first world country. You are in this grey area, where no rules apply.

“I went into Colnbrook thinking that everything was just a mistake. In detention, all you do is try not to die. You learn to never open the letters you receive from the Home Office before you go to sleep, because otherwise, you won’t sleep.”

“If you survive, you will never be the same person because an important part of your life dies there. The other part of your life that you are left with, you still carry these things with you. It’s never ending.”

50-yr-old asylum seeker (undisclosed country) Detained for 9 months

“The Home Office is not accountable for anything. It’s a game. They are just gambling with your life, and they play with it.”

“It’s like you [Home Office] take a 95-yr-old man and you put him in a boxing ring with a 20-yr-old man. What do you expect? He’s going to get knocked out. Isn’t he? You put this burden on vulnerable people and you sit down somewhere and you just watch me and make fun. You already know what the answer is. It’s David vs. Goliath.

“You can release me. Why are you keeping me? You just watch me. You refrain from releasing me because you don’t believe. I’m a human being and you still make fun of me. You are the one who kept me, who put me in there. You are the ones who the burden should be on, not me. What is your interest? Is your interest to give people a chance to legalize their stay or is your interest about victimizing people? Is that it?”

“I’ve always tried to be positive. I’ve always dreamt to show love to people and receive love back as a human being. But, most of those things they want to instigate in the minds of people is hatred. They couldn’t push me to that. No matter how hard they tried, they couldn’t push me towards feeling hatred for other people. But if you ask me, they pushed me to the extent that you start to question yourself, to question, What is humanity?”

36-yr-old man from West Africa. Detained for 18 months.

Both men are members of a group called Freed Voices. Members of Freed Voices have all experienced immigration detention in the UK. They share their stories to seek reform and so others have a greater understanding of the realities of indefinite immigration detention in the UK.

“Detention is a mental torture. It’s just like a nightmare. Sometimes it comes again. I say, Ahh, I’m now in detention still. Still I don’t have freedom. You just walk with fear. You don’t know where, where you are heading to.

“In prison, you know you are spending time. Six months … after six months, I have to be released or be deported. In detention, it’s indefinite. You don’t know when. I was there for three and a half years, so I have no purpose.”

“I’m in limbo now in the United Kingdom. They don’t allow me to work. I’m just in limbo. You can’t do anything. It’s very hard and all these things are psychological mental torture for you and you want give up on life. And when you give up on life, game over. You are nothing again.”

50-yr-old man from Guinea. Detained for three and a half years.

“Being put in detention was the second time I felt like I was killed in this life. The first time was what happened to me after I fled my home country. That first time, somehow, someone resuscitated me by giving me a way out. And I made it here to the UK. Here, I didn’t see a way for someone to resuscitate me and bring me back to life. It was like I was in a morgue for so many years. But somehow, somebody gave me a chance to live.

“So many things happened in detention. The psychological effects today, I’m still feeling it. I’m out of the detention centre but the detention is not out of me. I still sleep and I hear the sounds of keys rambling in my sleep. It’s like flashbacks. The noise. The smell of the food. The environment.

“In detention, you are the lowest of the lowest. There is no lower you can go. That is the lowest you are. And at the same time, you just survive for the next day and the day after and after. “

“Sometimes I say to myself, I wish the memories would be flushed away. I wish everything that has happened to me here and before would be flushed away so that I can become a new person. But it’s not possible. It can never be.“

37-yr-old asylum seeker. Detained 7 times over 5 years.

“I went to go report and they asked me to go to another room. When I went into the other room, there were several men waiting for me. They transported me to Yarl’s Wood.

“While I was detained, they tried to deport me several times. Several times, my deportation was cancelled a day or two before it was scheduled to happen. The last time, they actually walked me onto the plane. My hands and my feet were cuffed. My seat was in the last row of the plane. Four big men walked me all the way back so that everyone on the plane could see me. Every person looked at me, and I was like, I’m not a criminal! But they made everyone think I was. It was humiliating and I felt terrible. I started yelling and crying and you could tell people on the plane were thinking, Why are you treating this woman like this?

“Eventually they took me off the plane, but they treated me like I wasn’t human. They are people who have sons and daughters and wives and fathers and mothers, just like me. Would they want people to treat them like this? Even today, I’m still afraid. I check in and you never know what will happen.”

Asylum seeker from Central Asia. Detained for 6 months.

“I’ve been in detention for about six months. It was horrible. It’s like being locked in a cage. It can take months, one year, two years. You don’t know. You just keep on waiting. Hoping one day you will get out. When you are locked up in detention, there's no hope. You just pray. Where are they going to take me? I don’t have nowhere to go. [As a stateless person] it’s still the same way when you are out. You still don’t have your passport or your documents. And you are still worried. And stressed.

“If you are there [in detention], you are just there. Nobody is there to help you out. The government’s not interested, because they don’t know where you come from. And you don’t have a country that fights for you and says, Oh, we are fighting for him. It’s just like the world abandoned you. Like you’ve lost everything. Nobody listens to you no more.”

38-yr-old man from West Africa. He was brought to the

UK as a young child but has never had documentation.

He spent 6 months in immigration detention.

This 40-year-old man is originally from China. He fled China and arrived in the UK nearly 20 years ago. Since arriving in the UK, his asylum claims have been rejected and he has lived on the streets, homeless and destitute. He's been in immigration detention six times.

”They have tried many times to deport me, five or six times. But they can’t. I’ve probably spent around eighteen months in detention over the years, but I’ve been homeless much longer. In detention, there is no freedom. And you are made to feel like a criminal. The police or Home Office officer said, ‘because you are here illegally it is a criminal offence,’ and I told them I didn’t do anything criminal.”

Originally from Zimbabwe, this man fled during the country's political unrest. He arrived in the UK ten years ago but his asylum claims have all been rejected. He has spent almost 20 months in immigration detention. A deportation order was initiated and he signed a voluntary return, but the Zimbabwe Embassy refused to recognise him as a citizen, leaving him stranded in the UK.

“For those who have no citizenship, they are in a limbo, because no one wants to believe them. The authorities don’t want to believe them because they say, How can you say you are somebody who doesn’t have proof where he comes from? The onus is on you to prove where you are from. You must be from somewhere! But even though you are telling them where you are from, they don’t accept you.

“You are passing time. You cannot plan. You cannot do nothing. Like you are not existing. The country I have gone to has refused to recognize me. You just don’t know where to turn to. You're like in a river and have been left to float about. There is literally nowhere. You are going nowhere.

“My first time in detention, I was thinking, It will probably be a few months, and I will be out of here. But it is like an indefinite prison because you do not know when you are going to get out. You have nightmares. Sometimes you shout out in your dreams because of the way you are feeling… you are not like the kind of person you have been.”

“It’s on a road that is not open to the public at the airport and you are behind a barbed wire fence that is three meters high. As I drive in, I mentally take a breath and say, All right, I’m going in. This is what you are going to do.”

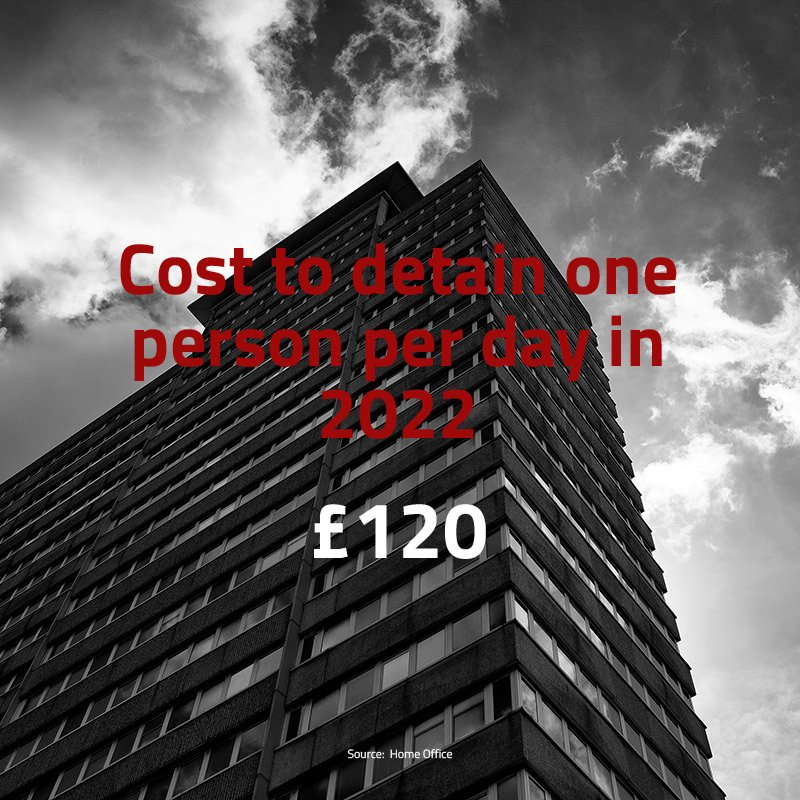

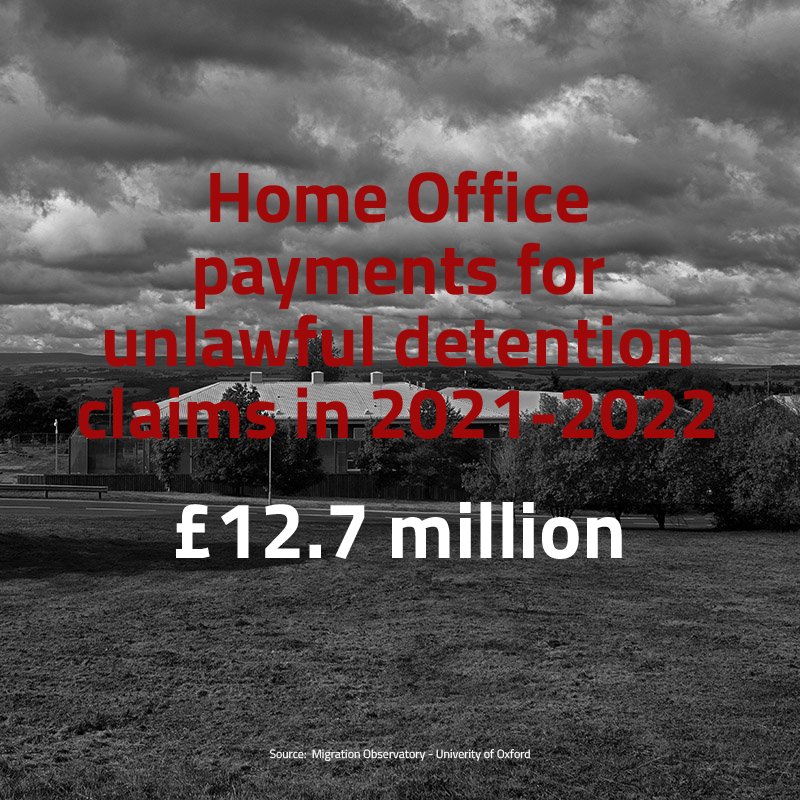

“I’m driven partially by anger. I’m angry at the situation and that there are people who are being detained under similar circumstances that were detained 25 years ago. Does that mean with another 25 years, there are going to be people detained under the same system? A system that doesn’t work, costs a lot of money and really is quite useless? At the moment, most people who are detained in immigration detention are released.

“What was the point of holding them here? It makes no sense whatsoever! And holding people in detention is just so bad for them. Their mental health deteriorates so quickly. You can watch someone’s mental health over weeks deteriorate. Each week, they’ve gone a step down. And you think, What are we doing to somebody if we are holding them like this and then after 6 months or whatever, we release them? Who is it satisfying? Is it a political act? In many ways it’s vindictive. It’s harmful.

“I think one of the common things someone in detention says to me is, What can I do? Which is an illustration of how isolated they are from the outside world and also from help. I try to build a relationship with people by saying, What do you need that I can help with? I can’t get you out of here as much as I might wish to, but I can’t. What do you need that I can help with? Do you have enough clothing? Do you need underwear? Do you need something to put on your feet when you go to the shower? These are not big deals, but they are some of the indignities of life in detention. Why not try to help?

“I must admit there’s a relief to get out and go away from these places. I’m very conscious of the fact that I can get out and go away and I usually have a vocal rant in the car on the way home about why this place exists and why it continues to do what it does because you’ve seen someone crushed by it as you’ve talked with them over the last half an hour or so. You can’t understand why that’s necessary. That’s why I shout. It just seems so pointless.”

John, Volunteer Visitor, Gatwick Detainees Welfare Group

Located on a private road bordering Gatwick Airport outside of London are two immigration detention centers: Brook House IRC (200 meters to the left in this photo) and Tinsley House IRC (400 meters to the right). Together, the two detention centers can hold over 600 people.

“The first time I visited someone in immigration detention, I was at a loss for words. And I think I still am in many ways. What do you say to somebody who’s in that situation? How can what you do help them? The only thing you can offer is some sort of hope. You can say, I can assure you, you will not always be here. I don’t know what is going to happen to you, but you won’t always be in this situation. While you are here, I want to see you and talk and listen.

“I think the isolation is deliberate and it’s very profound for many people in detention. They will have never experienced anything like that. Many of these people would have lived in this country for a long time. They have families here. And then suddenly, they are transported into this, this no peoples place. It’s outside of anybody’s understanding. They don’t know where they are. They know they are at an airport but they won’t understand where exactly they are. It’s dehumanizing and very very unsettling.

“The people inside are going through difficult challenging situations and you can see their humanity being drained away. Their autonomy is being drained away week after week.

“You know they call these places, Removal Centers!”

Mary, Volunteer Visitor, Gatwick Detainees Welfare Group

A colleague and Rudy from the organization Bail for Immigration Detainees (BID) take the bus to visit clients detained in Harmondsworth Immigration Removal Center at the Heathrow Airport in London.

“When I’m going to the detention center, I think about what’s ahead and what it’s going to be like in the detention center, the ordeal of stepping from the world into essentially a prison environment.

“Who are you going to encounter? What kind of situation are they going to be in? Are they having an acute mental health crisis? Are they missing family or fearing deportation from the UK and terrified of that? All of these things are going on. You just don’t know who you are going to encounter that day and what it’s going to feel like.

“Most of the people detained are already vulnerable and all of the laws governing detention are really stacked in the favor of the Home Office. When you are in detention, there are so many things that count against you and make it really difficult to access your rights and access justice.

“Also, a lot of the people have already experienced trauma. Detention is a kind of trauma in itself and for people who have been through things like human trafficking, forced labour or torture, detention is a reminder of that experience. People become re-traumatized as a result of detention. Their mental health deteriorates a lot.

“People don’t realize how pointless detention is and how in a very very small minority of cases detention actually fulfills its stated objectives and that is to remove people from the UK. Detention doesn’t do that. There’s the question, What does detention actually do?

“People might assume that the Home Office is detaining people for a reason because they have broken the rules or they need to be removed, whereas the reality is it’s an expensive way of harming people and achieving very little from the perspective of government policy. Probably people don’t know that. Most assume it’s a government department doing responsible things on the basis of evidence because they need to do it and actually that couldn’t be further from the truth.

“I get a lot of benefits from being a citizen of the UK and I feel uncomfortable about that in the work that I do, but it’s a fact that you are confronted with that’s unchangeable. There is that uncomfortableness but I think the most important thing is to use that privileged position to further the rights and recognition of people who don’t have that.“

Rudy, Former Policy and Research Manager, Bail for Immigration Detainees

Staff and volunteers work the BID ‘advice line’. They answer calls and assist immigrants detained across the UK.

“Our advice line is open from 10:00am to 12:00pm every Monday to Thursday. At 10:00am, the phones immediately start ringing and they ring continuously until 12:00pm.”

“A lot of people who call into the advice line are very vulnerable and even if they are not vulnerable themselves, they are in an incredibly difficult situation. The virtue of that, they come here to the UK and they are detained in immigration detention, it’s exacerbating their trauma and not allowing them to recover, so when they call us, most of them are very vulnerable.

“Working in this area can be difficult, precisely because you are in direct contact with them and their stories. A lot of the things they share are so heavy and you are the only one listening to them. There are some days when you just feel gutted by what you are listening to and frustrated in the inability to help because of the complexity and the hostility of the environment.

“I carry home a lot of my clients’ stories. It’s not easy to shut it all off. I find myself coming home and still thinking about what they have told me. I can see the resilience in them and it is quite inspiring. Sometimes it’s so inspiring. Other times it is grim and it makes you feel hopeless and completely lost without any faith in the humanity of the system.

“I’d say we experience more defeats than victories. Defeat is so difficult to deal with and we feel the defeats in a very strong way.

“I feel like we have a double purpose. One thing we do is give people an opportunity to be listened to and to have a voice. Our clients often don’t have anyone to talk to. They call us and they want to be heard and to get an update about their cases and they feel heard through the advice line. They say, I know the advice line is always there for me.”

“I had a man call and tell me, I’m sorry I call every day, but I don’t have anyone to call. I know you guys are always there to answer my calls. He said, In my cell, there is a little bit of light that comes in, in that light I see you guys. If you don’t answer my phone calls, I’m in the dark. “

Ines, ‘Advice Line’ supervisor, Bail for Immigration Detainees

Community members of the No To Hassockfield Campaign walk together and carry flowers in an unannounced visit to the Derwentside Immigration Removal Center. Their visit took place during the time of mourning days after the death of Queen Elizabeth II. Located in County Durham outside the village of Medomsley, it was the site of a former facility for young men, notorious for decades of abuse throughout the 1960s, 70s and 80s before closing in 1988. It then served as a prison until 2015. In late 2021, Home Office repurposed the facility into an immigration detention center. It has the capacity to detain up to 80 women.

“It is a site of historic abuse. It’s generally hidden away from public view. It can’t be seen from the road. In a way, it hides a shameful secret both past and present.”

“There hasn’t been a history of refugees, asylum seekers or migrants being locked up in the northeast of England. It’s the first time we have this on our doorstep and we’re committed to our campaign until it’s shut down.

“This was one of the few times we have been able to get access beyond the front gate barriers and walk down to the centre itself. We decided to suspend our regular demonstrations but we were worried the women inside would feel abandoned, so the act we made was a somber and sober act of taking flowers to the women, to demonstrate our friendship and to pass them flowers at a moment of national mourning.

“The place is a site of mourning itself. People died there. People were tortured there and I think the women who are there are in deep distress actually. Our action was contemplative, meditative, but it was also a bold action of resistance that reached out with love and solidarity. Taking the flowers to the women means they know they haven’t been forgotten about.”

Julie, No To Hassockfield Campaign

Napier Barracks is an old military barracks located on the outskirts of the town of Folkestone in Kent. In September 2020 it was repurposed as a site to house and hold asylum seekers. Originally built in the late 1800’s, the dilapidated barracks now holds hundreds of asylum seekers. In mid-2021, the High Court ruled Napier Barracks did not meet even the minimum standards for housing asylum seekers.

“How can someone be proud about removing someone that has gone through difficult times and you say you’re going to be proud of removing them to Rwanda? There is no sympathy. Nothing. No empathy. That tells you how cruel the system is.”

43-yr-old asylum seeker. Detained 7 times over 5 years

Several hundred people demonstrate outside the Royal Courts of Justice in central London. They demonstrate against the UK’s proposed policy to deport some asylum seekers in the UK on one-way flights to Rwanda, where they will have their UK asylum claims processed. Demonstrators consider it a form of ‘offshore detention’.

“The accommodation outside of a hotel might be better than being in a hotel. For sure. But still, the psychological stress runs through in any situation. It is very, very, very difficult.

“It’s damaging. When you are in this kind of place psychologically, in a hotel, at the same time you have your family pushing you more. You have to take the responsibility for them and take the stress for them. You share the stress with them but all of this falls on your neck. And, you can just imagine how much it is. Eventually, you have to stay alive for them.

“Someone asks, How are you? You say, I am fine. Yet behind your answer, there are tears running down your face.

“Such kind of stress…for me in my whole life, I have never ever thought about killing myself except during this time. By that time, I got to know, a person can come to a decision of killing themselves because he’s actually fed up. Has no way out. Like you have been trapped in a corner without knowing what will happen after five minutes. Not tomorrow. But five minutes you don’t know.

“Suicide, attempted suicide, being drawn to a point where one starts to hate others, all of this I believe the Home Office is responsible for.

“I wanted to go visit a family member but I could only see them for part of the day because I had to return to the hotel that night because I was not allowed to be out for more than 24 hours. I had to report.

“It made me feel as if there was someone forcing you, like they had a rope around your leg, so they could pull on you at anytime. Often you have an asylum claim in process and you feel that by breaking this rule, it will affect your case. So, you have to be very careful. They control. If you want it or not, they control you. You fear. You’re scared. You fear all the time and you don’t even know about what. It is very disturbing.”

Asylum seeker from Sudan

Placed by Home Office into a hotel for 4 months.

“When I asked for asylum, the border official’s face changed. He told me, Why are you here? Then he told me, We know why you are here. There is free food, free healthcare and everything is free here. That’s why you are here. By this time, he was signing some documents. It really hurt me. He told me I was here for the money, like I don’t have any money and I was looking for everything to be free. And it has nothing to do with that. It’s related to security. That was my first interaction with the authorities. I felt like crying.

“But, the immigration officer is innocent. I cannot judge him for why he thinks this way toward migrants. My anger was toward my own country. They are the one so put me in this situation, They changed my life upside down. But what he said will be stuck in my life for a long time. It really made me feel like, Ok, now I know where I am. I know where I am in the chain of society here. We’re at the lowest part of the chain here, unfortunately.

“At midnight we were moved to a hotel by the airport. We thought we would only be there for one week. We were there for six months. In one room with two kids, husband, not knowing what is going on.

“You ask yourself, Why am I in a hotel? This is not a normal place where a family can be. Who stays in a hotel for six months? You cannot go out without permission. You have to sign in and sign out every time you leave. It’s a kind of more comfortable detention centre.

“In the hotel, there were about 300 people. Africans, people from Iran, Afghanistan, Syria, South America. The whole world was there, and you don’t know how people are. It wasn’t safe. You don’t want to let your child walk to another floor because you don’t know who they will encounter.

“There are families who are moved from one hotel to another every month. You don’t know if you will stay, move into an apartment or move to one hotel, then another and another and another, packing and going, packing and going. The anxiety of not knowing what is going to happen is one of the most tiring things. You put your head on the pillow at night and you feel so tired.”

“A hotel, it may look comfortable but it’s like an open psychological prison.”

Asylum seeker from Turkey

Placed by Home Office into a hotel for 6 months with her family.

“It’s another kind of detention and I think for them it is another form of detention.”

“What people hear about the situation for people housed in the hotels, this is very different from the reality. They can be there for one or two years. After a certain amount of time there is a huge amount of stress on someone’s mental health. Not only are they waiting on an asylum claim to be heard, but also the monotony and intensity of families living in one room with no finances to actually be able to escape from that room where they are free to come and go from these hotels. They have no choice in their life, in that moment and anything. We as volunteers try to support and soften this for them.

“As time goes on, living in one room can cause huge strains on relationships within the families. You begin to see the cracks in relationships. But, you also see the stresses and strains on relationships across the residents within the hotels.

“People come here already having suffered trauma in their lives, some of which we have no experience of or knowledge of in our own personal lives. I still hear things that shock me to the core, that human beings can do such things to another human being.

“Life in hotels is tough and we are constantly being asked if there is anything we can do, but we are just a humanitarian charity. We have no power and that’s hard, because you feel powerless. I think I’m a fairly resilient person. But it does have an impact because you feel so powerless to help in different ways. You want to change the way things are for people but all you can do is try to support them on their journey.”

Denise, Volunteer support worker assisting asylum seekers in hotels

“I had nothing in Kuwait. The government denied me rights and a future. So I had to leave. I left and came to the UK. I was in the UK for several years, and they refused all of my asylum claims. It became too much so I had to leave the UK. I bought a ticket, went to Heathrow and immigration detained me.

“My life was over. The judge asked me, Why did you use a fake passport? I said, Home Office tied my hands and threw me into the ocean. How am I going to swim?”

“If you are thirsty and I put a glass of water in front of you and say Don’t drink that! You sit thirsty in front of that glass of water for 3, 4, 5 days, you will drink it and what will happen? I said, I’m thirsty. I am thirsty to have a normal life. I ask you so many times to give me a drink but you don’t let me.”

“Everything leads to nowhere. There is no solution. I try to keep myself settled and clean. I’m trying to apply for work, but I’m not allowed. I want to do volunteer work, but I’m not allowed. I want to go to university in London, but I’m not allowed. I’ve tried to get a driver’s license, but I’m not allowed. I want to be a normal person. Is that too much to ask?

“When I came to the UK I had plans and dreams. Now look at me. I have nothing. It is like a spider web. I am trapped and any move I make, I get stuck even more. I get stuck in their web and there is no way out.”

Asylum seeker from Kuwait. Detained for over six months

Campsfield House Immigration Removal Center located in Oxfordshire detained up to 280 people. It was closed in late 2018. Photograph from 2017. In mid-2022, the Home Office announced plans to redevelop and reopen Campsfield House to detain up to 400 men per day. Members of the Coalition To Keep Campsfield Closed demonstrate outside of UK Parliament in September 2022.