"In detention you don't exist anymore. You have no one and even if you are a recognized refugee, you can be arrested and detained here.

"A darkness covers you and your life, and it lives with you."

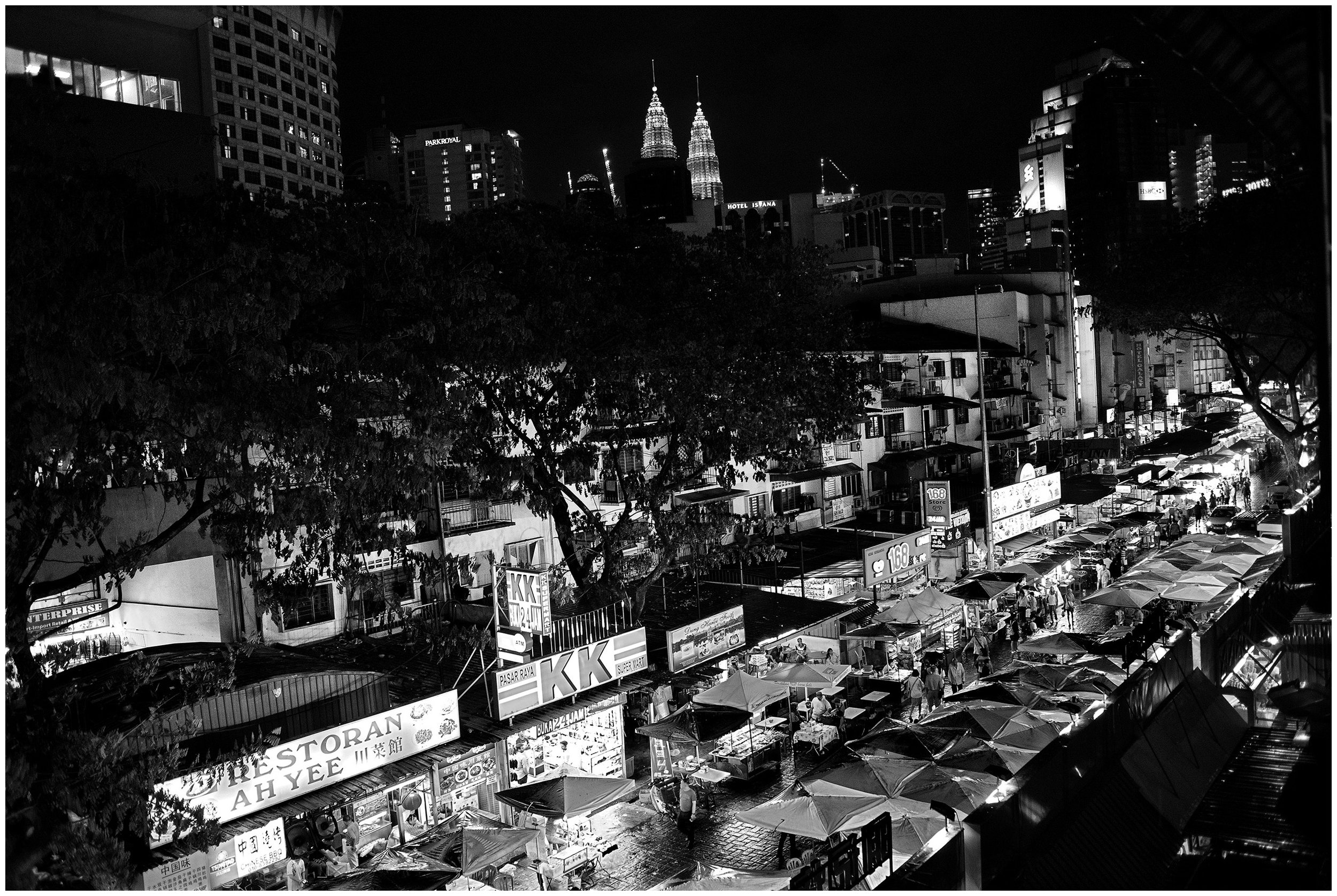

MALAYSIA

A DARKNESS COVERS YOU

Like many young men in the Chin State in northwest Burma (or Myanmar), 20-year-old Dawt Cung had been forced by the Burmese military to serve as a porter, moving military equipment and camp supplies. Decades of forced labor, abuse, arbitrary arrest and constant harassment from the Burmese army had forced many like Dawt Chung to flee their homes and seek asylum in other countries throughout the region. In mid-2015, Dawt Chung had had enough, so he made the difficult decision to leave family behind and seek sanctuary in Malaysia.

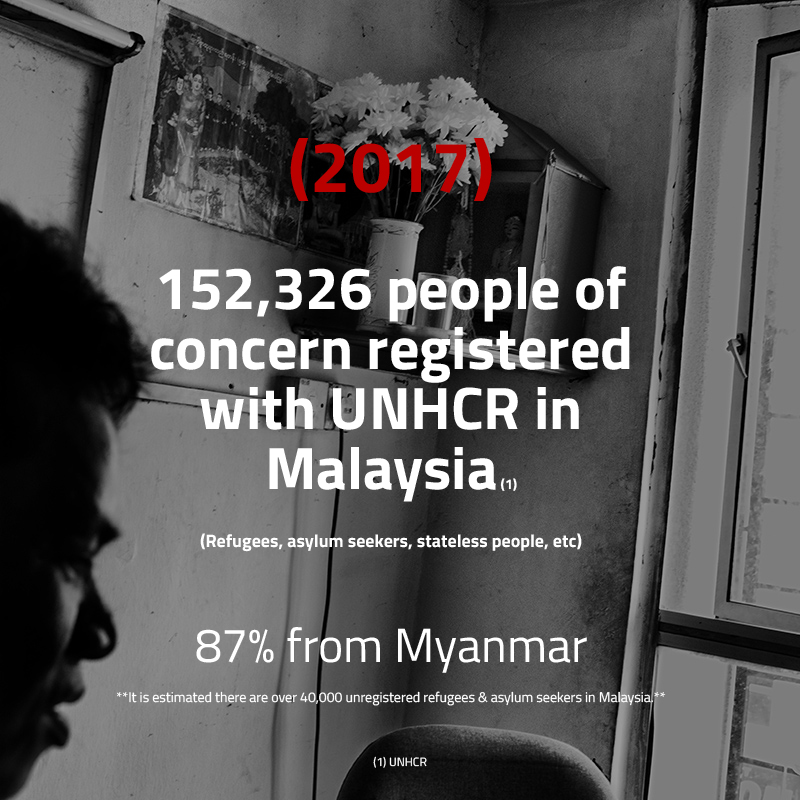

For decades now, Burma has been the largest producer of refugees in Southeast Asia. Ethnic groups indigenous to Burma like the Chin, Mon, Rakhine, Rohingya, Shan, Karen, Kachin and Karenni have all been subjected to conflict, human rights abuse, ethnic cleansing, religious persecution or the denial of any number of other rights. For decades, Malaysia has been the adopted sanctuary for many. According to the UNHCR, of the 152,326 registered refugees, asylum seekers and stateless people in Malaysia in 2017, 87% (133,580 people) are from Burma. Rights groups in Malaysia like Penang Stop Human Trafficking Campaign estimate there are an additional 45,000 still waiting to be registered.

Arriving in Malaysia, Dawt Cung made his way to Kuala Lumpur and lived with his uncle, who had fled Burma to Malaysia in 2009. Without legal status, he got a job in Malaysia’s enormous shadow economy, working construction (a job common for many refugees and undocumented workers in Malaysia). Although free from the abuse back home in Burma, life in Malaysia proved to be equally challenging.

Malaysia is not a signatory to the UN Refugee Convention and its unsympathetic immigration laws do not recognize the difference between a refugee, asylum seeker and stateless person with that of one of the estimated 2-4 million undocumented migrants living and working in Malaysia. All shoulder the stigma of ‘illegality’ in the eyes of Malaysian policy. As a result, refugees and asylum seekers have no legal status in Malaysia and no right to protection as well. Regardless of being registered with the UNHCR or not, Malaysian policy has left tens of thousands, vulnerable to exploitation, abuse, arbitrary arrest and detention.

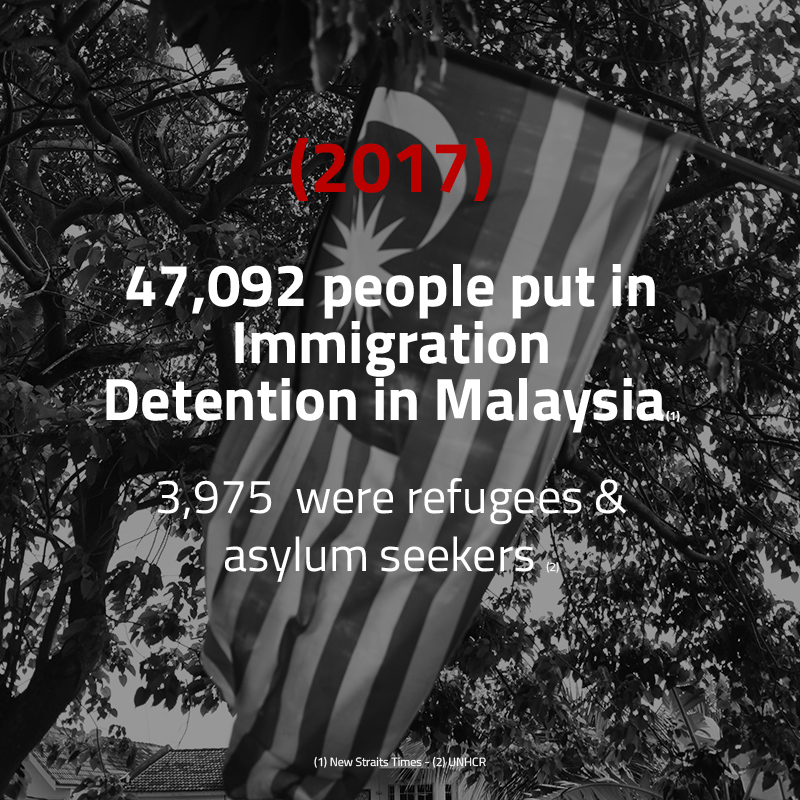

On February 17, 2017, two years after arriving in Malaysia, Dwat Cung was arrested at his workplace during an immigration raid and placed in one of Malaysia’s fifteen immigration detention centers. In 2017, Malaysian immigration authorities conducted over 16,000 immigration operations, which led to the detention of over 47,000 men, women and children throughout the year.

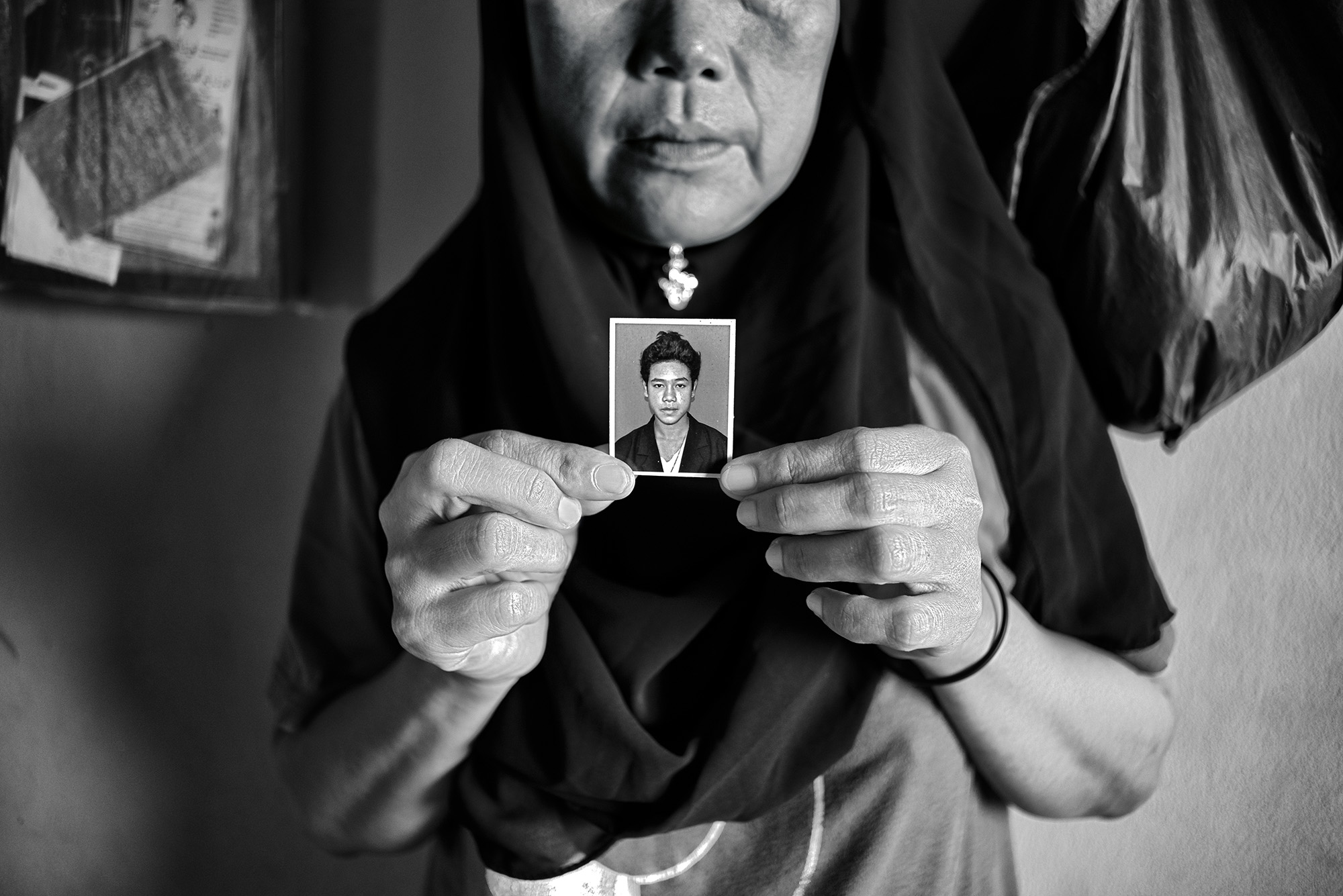

"I was the one who had to take care of him and look out for him. People say he will spend 3-4 months in detention then they will deport him back to Myanmar.”

Dwat Cung’s uncle says as he holds a photo of his nephew.

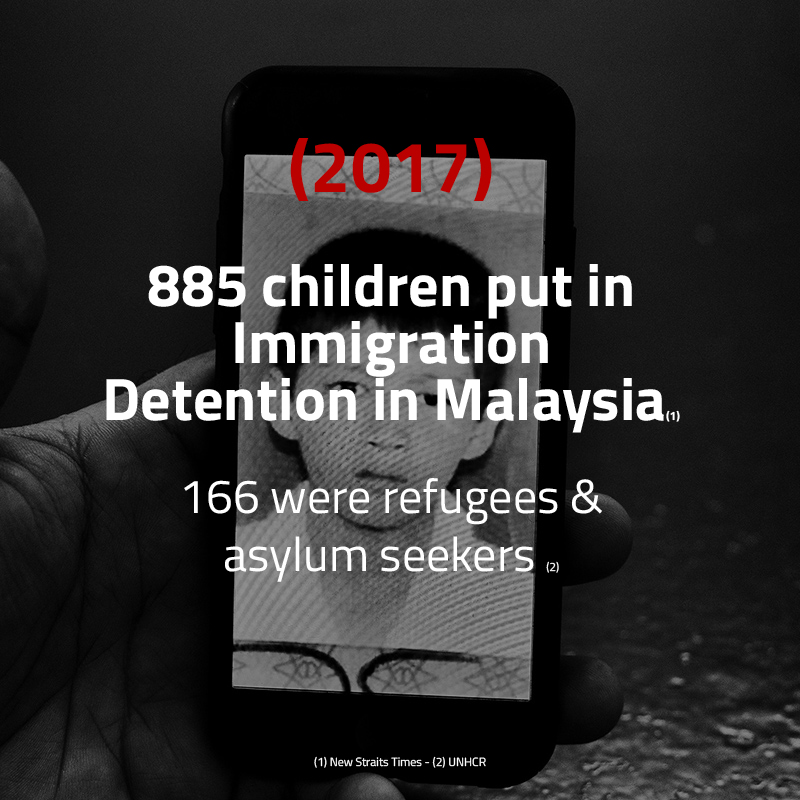

While the detention of refugees and asylum seekers declined from 2016 to 2017, almost 4,000 were arrested and placed in detention in 2017, including 166 children. In a report published by Save The Children in 2017, the average amount of time spent in detention in Malaysia in 2016 was fourteen months, although there is no maximum amount of time someone can spend in detention in Malaysia. As a consequence, a constant state of fear along with the looming threat of detention, permeates throughout the day-to-day life of refugees and asylum seekers in Malaysia.

“We live with fear of being arrested,” the uncle describes. “What will happen to my family if I am detained? We live with fear all the time.”

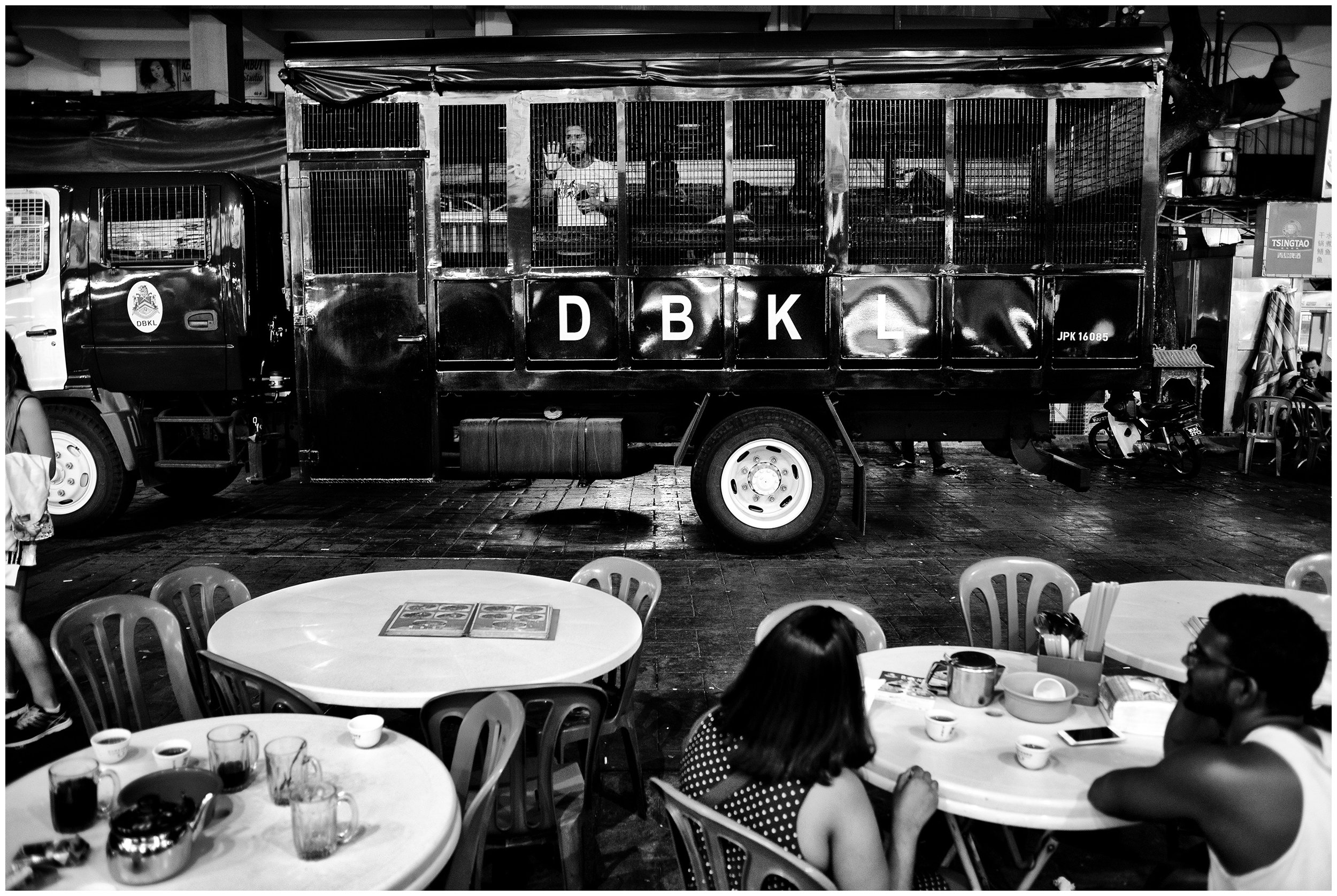

"Between 50-100 immigration officers and police arrived last night and went from one apartment to the other asking to see everyone's documents. It went on from 2:00am to 3:00am. At least 100 people were arrested. She was staying in a small room. They were banging on the door to the apartment block downstairs. Eventually they broke the door and then broke many of the doors to our apartments.

"She was so scared of being arrested she climbed up into the ceiling and hid there until they left. After they left she fell through the ceiling."

Man from Chin community describes an immigration raid in Kuala Lumpur on Feb 24, 2017 (below)

A 35-year old man (right) from the Rakhine (Arakanese) community sits on the floor of an apartment outside of Kuala Lumpur. A sticker of a Malaysian police officer decorates the apartment he shares with several other men.

In Burma, the authorities came to his family home and wanted to arrest him after his younger brother deserted his position in the military. He arrived in Malaysia in 2013. In 2014 he was working in a furniture factory in the Klang area of Malaysia when immigration raided the factory and arrested him. He spent three months in several different jails and was then transferred to Semenyih Detention Camp where he spent the next four months.

“When I was in detention, there were no windows and almost no light. Everyone felt so uneasy in detention. There were fifty of us from the Rakhine community in detention. When I heard the news that the UN was coming to the detention center, all of us felt some hope. The UNHCR registered me and gave me a document and I was released.

"But my UN document is going to expire. I have no idea what will happen after.”

Move the slider on the photograph (right) to see Semenyih Detention Camp. <>

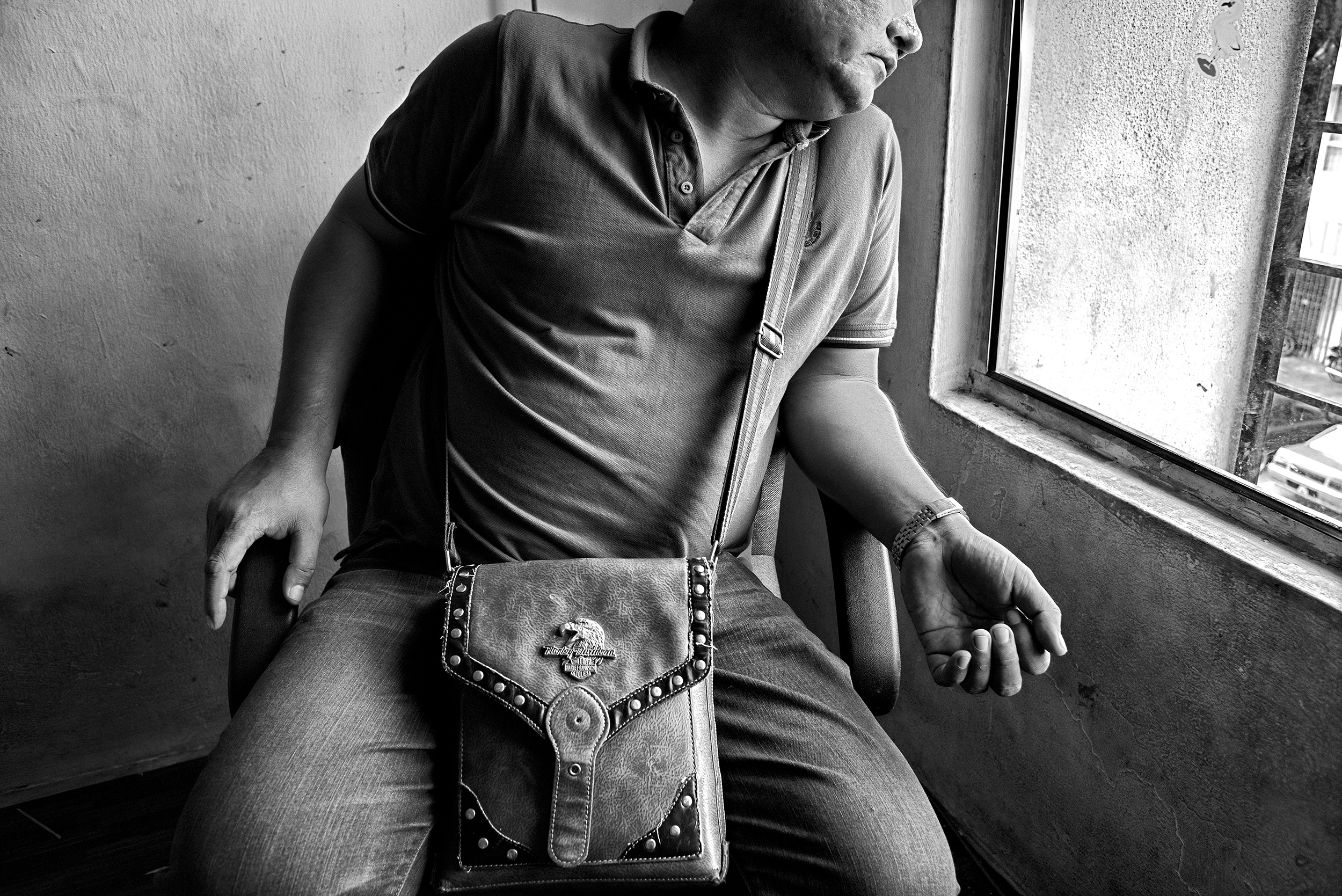

This man 37-years-old, (left) from the Rakhine community in Burma had a disagreement with the Burmese military and was put in jail for seven years. After he was released he fled the country and arrived in Malaysia in 2008.

Just after arriving in Malaysia he found a job working on a pineapple farm outside the town of Butterworth in northern Malaysia. The farm was raided by the citizen immigration forced known as RELA (now defunct) and he was arrested. He spent two months in prison, then eight more months in Langkap Immigration Detention Center before being deported back to Burma. After two months in Burma he returned to Malaysia. He was sleeping in the Alliance of Arakan Refugee’s office in Kuala Lumpur when it was raided by Malaysian Immigration. He was arrested a 2nd time. After two weeks in detention, the UNHCR helped get him released.

“Here in Malaysia, everyone is afraid. I have a UNHCR document now and I think that will help. But, I can’t think too much. I don’t want to get arrested again.”

A 25-year-old man from the Chin community in Burma sits in his apartment with his 6-year-old son. (right) He has lived in Malaysia for six years. His 24-year-old wife was arrested in February 2017 at her workplace and put into detention.

“We’ve been in Malaysia for six years. Last month, we were working together in a factory when it was raided by immigration. I have a UNHCR card but she doesn’t, so they arrested her. Several people were arrested. Some of them were released but she wasn’t.

“Since my wife was arrested and put in detention, my son is in a very dark place. He cries all the time. When he cries he says, Let’s go to my mom. I want to see my mom. He never leaves my side.

"All I think about is finding a way to get her out of detention. They sentenced her to ten months and I don’t know for what reason but this is too long.

“I talked with her on the phone and she was so scared. She shares a room with thirteen other people and she is the only one from Burma so she has no one to talk with. Now, I can’t contact her so I worry about her every day. I feel like death because I am so afraid of being arrested. We rarely go outside. Mostly we stay inside.”

Move the slider on the photograph (right) to see Lenggeng Detention Camp. <>

PHOTO GALLERY: Malaysian Immigration, police and plain clothes officers conduct an immigration Operasi in Jalan Alor on March 6, 2017. (one of the busiest street markets and tourist destinations in central Kuala Lumpur) Use arrows on right and left to navigate. <|>

"In Malaysia, we live in fear of arrest and detention. Immigration and police raids happen all the time. There is no warning. They happen anywhere at any time. In a factory, on the streets, in restaurants and when you get off the bus. I always look over my shoulder."

50-year old refugee from the Karen ethnic community from Burma. He spent four months in immigration detention

This 35-year-old woman (below) and mother of three children from the Kachin ethnic community from Burma now lives alone as a refugee in Malaysia. Conflict in her village in Kachin State and harassment from Burmese military forced her and her husband to flee to Malaysia with their small children in early 2014. At the time she was pregnant. After two months in Malaysia, she had an accident that caused an early delivery. She started bleeding and a friend rushed her to a clinic where she gave birth. The baby died during delivery. She was transferred to a hospital and after seven days in the hospital she was released.

“Immigration arrested me as I was released from the hospital.

"I spent one month in jail. I never saw a judge or went to court. Then they moved me to an immigration camp where I spent another six months. While in the immigration camp, I continued to bleed because of my delivery but I didn’t have anything. I didn’t have soap and I only had one pair of clothes. They never gave me anything extra to change into. I was released but eight months later, my husband was arrested by immigration. At that time, I was pregnant again. He spent one year in detention and was then deported back to Burma. I’m alone now with three children. Friends give us food.

"I work small jobs close to where I live. Now I avoid walking on the main road. I always walk through shops and the market to get to work.”

In December 2012, Burmese soldiers came to this man's village in Kachin State of Burma and ordered the men in his village to act as porters for the military. He ran away and was too afraid to return, so he fled to Malaysia. One month after arriving in Malaysia he was arrested in the town of Butterworth.

“I was working in a small shop and around 12:00am the police came to the shop and arrested me. I was kept at the police station for fourteen days, then taken to court. Because I didn’t have a passport and staying here illegally, they gave me six months and two lashings with a cane. They put me in Langkap camp. When I first arrived at the camp, I was put in a block which could hold only 100 people but sometimes there were 200 or even 300 people in the block. For new arrivals they didn’t have space to sleep. There were no extra clothes and no blankets and it was very cold in the morning.

"It felt like I had no more hope. Before then, I had never been in trouble. Then to have such a terrible experience in Malaysia. The UNHCR registered me while I was in detention. Then I was released. But when I got out, I felt so scared to be in such a situation again."

Less than one year later, he was arrested a 2nd time.

“I showed them my UN card, they said ‘No you can’t live in Malaysia with that document’. I was taken to the police station and I sat there for several hours. That night an investigator asked for my UN Card. I told him the man who arrested me kept it. He asked me what kind of UN document it was and I told them the UN had issued me the document when I was in Langkap. He said the document probably wasn’t genuine and that I couldn’t live in Malaysia with such a card. I went to court twelve days later. I spent twenty-one days in prison then was transferred to Semenyih Immigration Camp where I spent another three months. In Semenyih, I almost died of a stomach infection.

"After I fled from a very terrible situation back in Burma, I was so miserable because I had to go through such a horrible experience again in Malaysia.

"After the first experience of being arrested I thought I would not have to go through a similar situation again. I was relieved. But I was arrested for the second time and as I nearly died, I felt so desperate and so scared. That’s how I felt. I lost trust in people, unlike before.”

Semenyih Immigration Camp

This 60-year-old woman (left) is from the Mon community in Burma. She and her husband fled Burma and are both registered with the UNHCR in Malaysia. Her youngest child is 19-years-old and worked in the fishing industry. Malaysian Immigration arrested him and several others in late October 2016.

“I saw my son in detention and he looked like he was crazy. When I talk about him I get so upset. He’s a good person. Now in the jail, he is so stressed. He said, ‘Mother I want to get out of here. I have to go home.’

"I have to earn the money to visit my son. So, I have to get up early to cut fish. Then I move and cut fish in another place. And then another. When I saw him, he had a rash on his skin and he could not sit well. He told me, 'I’m in pain mother.' He was fat before, but now he has lost a lot of weight. His eyes were sunk in his head.

"All the money I get from work, I use to buy oranges for my son to eat. He said, 'Mother this is not enough.'"

This 45-year-old woman (right) from the Mon community in Burma has lived as a refugee in Malaysia for over a decade. She has a 17-year-old son who until mid-2016 remained with relatives back in Burma. After he arrived in Malaysia he started working in the fishing industry. He was arrested by Malaysian Immigration in October 2016. Everyone in his family was registered with the UNHCR. He was not.

"We came here because we life was very difficult. My eyes cannot see well. My son worked to support his mother. He was arrested after he arrived here seven or eight months ago. He went to school to grade eight. He can speak a little bit of English. After he arrived here I let him work because we have difficulties here too. He is young and I feel very sorry that he had to work.

"When I saw my son he had lost a lot of weight because there is not enough food. He had a rash on his skin and he wasn't sleeping. I am so upset because my son is not with me. I also cannot sleep because I worry about him. He is young. My daughter is so upset too.

"We used to live as one family. But now he is in jail. I cry when I think of him because he is not with me. He is so young."

Move the slider on the photograph (right) to see an activist from the Mon community holdinga photo of the young boy on his mobile phone. After seven months in detention, Malaysian officials deported the 17-year-old boy back to Burma. <>

This 24-year-old man from the Mon community fled Burma and has lived in Malaysia since 2010. He lives and works on a remote rubber plantation. Undocumented, he rarely leaves the forest for fear of arrest by Malaysian police. In early 2017, Malaysian immigration arrested his 22-year-old wife at the hospital and put both the mother and the newborn baby in detention.

“On the 16th, I paid the hospital. After paying, my wife was able to see the baby. They said the mother was not allowed to go home yet because she didn’t have a passport. The nurse said they had to inform immigration. On the 20th, immigration came to the hospital. I didn’t know anything about this. I came to collect all of the things from the hospital for the baby to go home, and I got a call saying she had been arrested."

“When I first saw the baby, I was happy but I’m worried because the baby is so young. We saw each other for only a few minutes and then we were separated. Now I am so unhappy in my mind. I don’t know when I will see them again and I’m worried.”

Originally from the Philippines, this 49-year-old mother (rights) has lived in Sabah for almost thirty years. Her son was born in Sabah but has never possessed documents. In October 2016, one month before his 18th birthday, he was arrested by immigration on his way home from working on a construction site.

"I don't know what to do. He is so young and has been in detention for so many months."

Move the slider on the photograph (right) <>- Families bring food, toiletries and other essentials to family members in Kimanis Detention Camp in Paper, Sabah.

Originally from the Philippines, this family has lived in Sabah, Malaysia for decades. Two of their relatives, both children ages 15 and 16, were arrested by immigration for not having documents and placed in detention. The family gathers outside the Manggatal Detention Center in Kota Kinabalu, Sabah.

A 16-year-old youth from the stateless Rohingya community fled Burma in 2014. Human traffickers kept him in a jungle camp in southern Thailand with other Rohingya for two months before releasing him to Malaysia. In December 2016, he was walking to a store to buy food when Malaysian police approached him and asked to see his documents. He had never possessed documents and was not registered with the UNHCR. He was arrested and placed in detention.

“There were so many in detention. 14-years-old,15-years,17-years. They were all Rohingya. The police arrested them for the same reason. They didn’t have UNHCR cards or any documents. In prison I felt so lonely. Even with other Rohingya in the prison, I felt so lonely.”

After four months in detention, he was released on bail and placed into an Alternative To Detention program run by a Kuala Lumpur-based NGO while waiting for his case to be heard by the Malaysian courts.